SFUSD’s record in Math is being assailed for two reasons:

First, it is “significantly off-track” in meeting the goal set by the Board of Education for improving Math proficiency rates. That’s not surprising because the goal is practically unachievable but it is good that the district is focused on something as practical as more kids learning more Math.

Second, the district’s course sequence for Math is under attack and a campaign is under way to “bring back Algebra in 8th grade.”

These two avenues of attack are focused on the needs of separate segments of the student population. The first is focused on those who are not proficient and seeks to make them proficient. The second is focused on those who already meet or exceed standards but whose ability to reach their potential is perhaps being hurt by the district’s policies. Both are important, but I’m only going to focus on the second today.

SFUSD’s Math Pathway

The motivation for SFUSD’s current Math pathway, which dates from 2014, is the belief that everyone, regardless of ability, should take the same Math class through 10th grade. Although the general public’s shorthand for the policy has always been “getting rid of Algebra in 8th grade”, the Math policy was merely the most visible part of a district-wide move towards detracking. At about the same time, SFUSD got rid of Honors classes in English and Science before 11th grade and abolished its Gifted and Talented Education (GATE) program. The belief was that mixed-ability classrooms would benefit all students. The district saw itself as in the vanguard of a movement that would sweep the state.

“San Francisco always goes first, the rest eventually catch up…Restorative practices…ethnic studies…universal health care in the city…gay marriage”.

Richard Carranza, Superintendent of SFUSD.

For a while, it looked like that would happen. The first draft of the new California Mathematics Framework made extensive references to the success of SFUSD’s experiment and, if approved as drafted, would have reshaped Math education across the state.

The momentum is now in the opposite direction.

Families for San Francisco produced a report documenting that many of the claims SFUSD made for the success of its pathway were false. (Disclosure: I was one of the authors of the report).

The second draft of the new California Mathematics framework removed all the references to SFUSD but still received such massive pushback from the Mathematics community that the whole framework is now in limbo.

Professors from Harvard, Stanford, Berkeley, and UCLA wrote a letter to the Board and the SFUSD Math department in June 2022 saying that “the idea that conceptual understanding is incompatible with acceleration is not supported by evidence” and that the policy’s “implicit suggestion that calculus is less important for university success today than it was in previous times” was also unsupported. They pointed out that “93% of incoming Harvard students have taken calculus or above in high school.” (emphasis added: courses above calculus, such as multivariable calculus, are offered in other public school districts and in certain San Francisco private schools but not in SFUSD).

In August 2022, a working paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research that examined data on tracking in all public schools in Texas found that “exposure to tracking...[has]…positive effects on high-achieving students with no negative effects on low-achieving students”

In March 2023, the first academic study of SFUSD’s experiment showed that “the policy ultimately did not increase access [to AP Math] but also did not restrict it…our evidence is consistent with the hypothesis that delaying Algebra I until ninth grade made it difficult for some students to complete the sequence of course prerequisites that would position them to take AP Calculus before graduating.” It continued: “large ethnoracial gaps in advanced math course-taking motivated this reform but did not change in the post-reform period”. SFUSD’s response was to say that it was going to “examine the feasibility of increasing opportunities to accelerate in high school. (emphasis added)

In May 2023, SFUSD said it would suspend the Math Validation Test (MVT). The MVT was administered to incoming 9th graders who had passed Algebra I in an online course or at a private middle school and wished to move straight to Geometry in 9th grade. The test had a very high failure rate and was seen by many parents as an attempt to limit the number of students who were accelerating. The district suspended it in response to a suit filed by parents who had seen Palo Alto Unified lose a similar case earlier in the year.

Experience from Other Districts

I thought it would be interesting to look at how other districts handle the issue of tracking and acceleration. When and how do they offer acceleration to their students? Do students have multiple opportunities to accelerate or are they out of luck if they decide later to accelerate?

Rather than pick my own set of comparable districts, I’m going to use the ones used in the recent report on school district finance by the Budget and Legislative Analyst’s Office at the behest of Supervisor Hillary Ronen. These districts are comparable in size to San Francisco and drawn from around the state.

As a little bit of background, there are two math course sequences that are popular in public school districts across the state. San Francisco uses the “Traditional” math sequence of Math 6 → Math 7 → Math 8 → Algebra I → Geometry → Algebra II → Precalculus → Calculus. Other districts use a sequence that blends the geometry material in with the Algebra material so that geometry no longer appears like a forced detour between two Algebra classes. This “Integrated” sequence goes Math 6 → Math 7 → Math 8 → Integrated Math I → Integrated Math II → Integrated Math III → Precalculus → Calculus.

Districts face the same challenge whichever sequence they use: a student who wishes to do Calculus in high school needs to cover eight years worth of material in seven years. Eight years of material in seven years is not very “accelerated” but what invariably happens is that the acceleration happens, if at all, over much shorter time periods. It generally takes one of the following forms:

doubling up: students can take two courses simultaneously that were designed to be taken sequentially. This only works in the traditional sequence where geometry can be paired with either Algebra I or Algebra II. Of course, many students in San Francisco have been combining their school’s Math 8 with online Algebra I but, since Algebra I is designed to build on Math 8, that is not an approach that anyone would recommend. This is also the most expensive approach since you need two Math teachers instead of one.

Summer school: students can take one of the required sequence, usually either Algebra I or Geometry, in the Summer. Again, this is expensive and few students really want to study in the Summer so take-up will always be lower.

2:1 compression: a course combines two years of material into one year. San Francisco’s course that combines Algebra II with precalculus material (whose concept has been borrowed by other districts) is one of the few examples of this. Cramming two years worth of material in one year is hard for both teacher and students. SFUSD’s compression course contains so little precalculus material that it doesn’t qualify as a precalculus course according to the UC. It is notable that San Francisco has never put forward any evidence that its compression course provides adequate preparation for Calculus. Are students who take the compression course able to do well on AP Calculus?

3:2 compression: a pair of courses that compress three years of material into two years. San Francisco does not do this but it is by far the most common way districts enable their students to accelerate. Examples include:

In districts that start middle school at sixth grade, Math 6, Math 7, and Math 8 may be covered in 6th and 7th grades, leaving time for Algebra I (or Integrated Math I) to be taken in 8th grade.

In districts that start middle school at seventh grade, Math 7, Math 8, and Algebra I (or Integrated Math I) may be compressed into two classes.

In high schools, Integrated Math II, Integrated Math III and Precalculus may be compressed into a two-year accelerated sequence.

It seems obvious that covering three years of material in two years is much less demanding for students than covering two years of material in one year.

Of the twelve peer districts,

one (West Contra Costa) offers no acceleration before high school and only doubling up or 2:1 acceleration in high school.

one (Oakland) in theory allows Algebra I to be taken simultaneously with Math 8 but in practice only supports doubling up or 2:1 acceleration in high school.

one (San Bernardino) offers a 3:2 acceleration sequence at the start of high school.

seven (San Jose, Sacramento, Elk Grove, Corona-Norco, Fresno, Clovis, and Long Beach) offer 3:2 acceleration sequences from the start of middle school. Of those, four also offer separate 3:2 acceleration sequences in high school. That all four use the Integrated curriculum may or may not be a coincidence. San Jose also offers a 5:3 sequence that gets from Math 6 to Geometry in three years.

two (Garden Grove and Santa Ana) offer Algebra in 7th grade and Geometry in 8th grade, thus enabling some students to be two years ahead of the standard schedule by the end of middle school. These districts start their course differentiation even earlier.

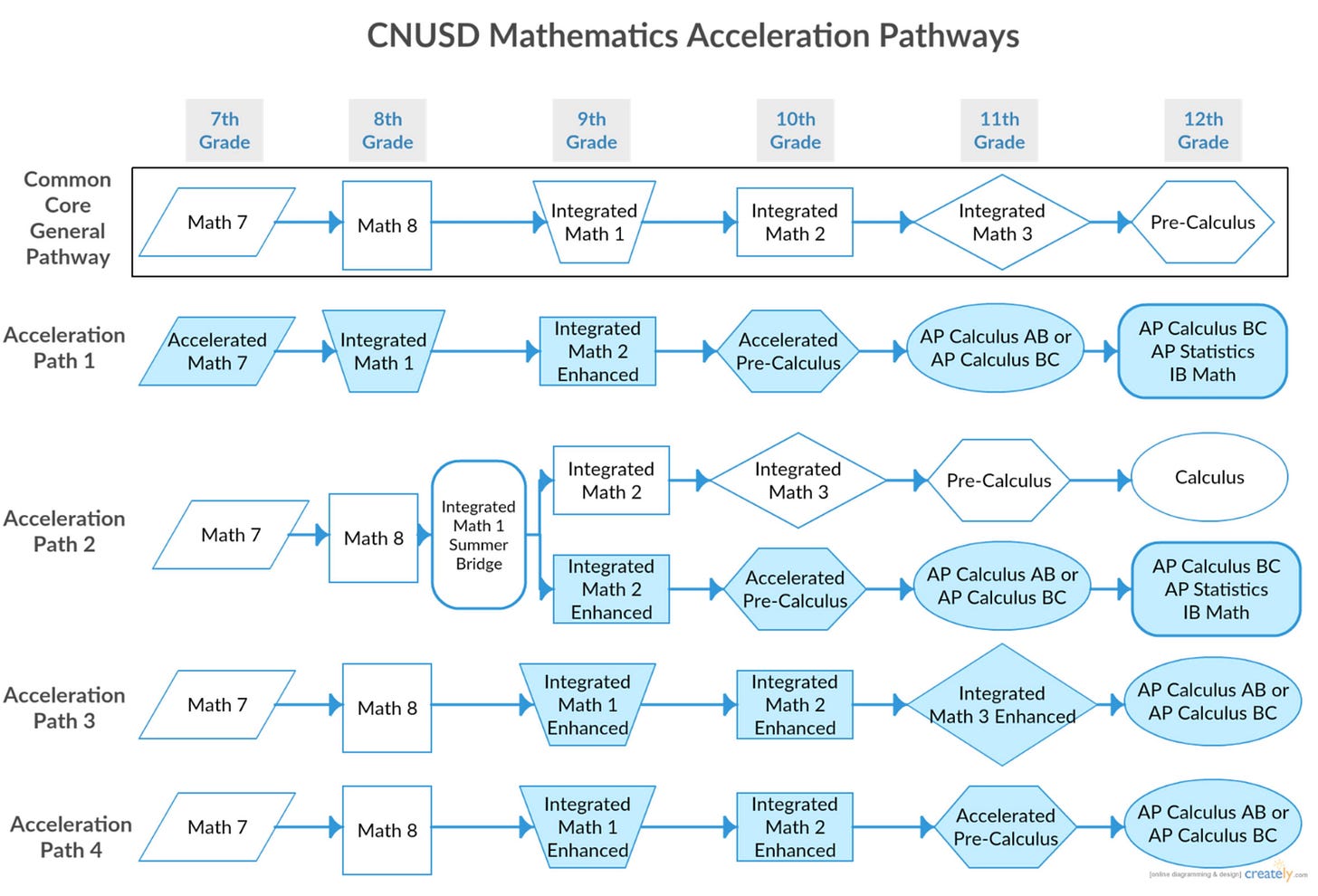

Here are some pictures of the pathways in different districts.

If San Francisco is serious about meeting the needs of its high-achieving students by revamping its Math pathways, it has lots of good examples to choose from. I am partial to the approach depicted in the Sacramento City pathway (Figure 2) because it allows students to accelerate as early as 7th grade or as late as 10th grade and still reach the same destination.

Appendix: Details and links for each district

West Contra Costa (56% Latino, 13% Black, 10% Asian, 10% White) has the most similar approach to San Francisco. The only acceleration options offered are doubling up on Geometry and Algebra II in 10th grade or taking an Algebra II/Precalculus compression course in 11th Grade. In a recent letter to parents for the upcoming 2023-24 academic year, they double down on advising students not to accelerate before 10th grade. Interestingly, their compression course is treated by UC as a pre-calculus course (i.e. an advanced math course) whereas San Francisco’s is not. Still, their two largest high schools just offer regular precalculus, not the compression course, which indicates most students don’t take it.

Oakland (48% Latino, 22% Black, 12% Asian, 10% White) is pretty similar to West Contra Costa. Students can double up on Algebra I and Geometry in 9th grade or they can enroll in a course that compresses Algebra II and Math Analysis (their version of precalculus, it appears) into one year. The novel aspect to their published policy is that they allow Math 8 and Algebra I to be taken as two separate courses in one year (see this presentation, pages 13-15). Although that is the published policy (Board Policy 6143.5), I was unable to find evidence that any Oakland middle school actually offered Algebra I. I found one that use to offer it as a zero-period class that met three times a week instead of the usual five but that school stopped offering it “temporarily” during the pandemic.

San Jose (53% Latino, 22% White, 14% Asian, 2.5% Black) offers lots of opportunities for acceleration in middle school. A sixth grade student can take Accelerated Math 6 and then move straight on to Middle School Algebra I and then Geometry in 8th grade. Students who find Accelerated Math 6 challenging can go into Accelerated Math 7 and then take Middle School Algebra in 8th grade. A student who took the regular Math 6 can also jump to Accelerated Math 7 and then to Middle School Algebra. Students who took the regular Math 6 and Math 7 haven’t missed the boat. They can take a summer school “ramp up” course which covers enough Math 8 material to enable them to take Middle School Algebra in 8th grade. Finally, a student who takes the regular Math classes all the way through middle school can also take a summer school “ramp up” Algebra class and move straight into Geometry in 9th grade. That’s five separate middle school paths, offering acceleration after 5th, 6th, 7th, and 8th grades, that position students well for Calculus in 11th or 12th grade. It does not offer separate acceleration in high school.

Sacramento (41% Latino, 17% Asian, 16% White, 14% Black) uses the Integrated Math curriculum and starts middle school in 7th grade. It offers two separate course sequences that each combine three years of Math into two years. In 7th and 8th grades, a student can take Compacted Math 7/8 followed by Compacted 8 / Math I. In high school, a student can take Math II Plus and Math III Plus which compress the material from Math II, Math III, and Precalculus into two years.

Elk Grove (28% Latino, 27% Asian, 18% White, 11% Black), which is also in Sacramento County, has an almost identical approach: two separate sequences that combine three years of Math into two. One sequence can be taken in middle school, the other in high school. This approach has two nice features. First, students can get on the path to Calculus as late as 10th grade. Second, students who take both accelerated course sequences are able to take AP Calculus BC in 11th grade and then a multivariable calculus class in 12th grade. Only private high schools offer multivariable calculus in San Francisco.

Corona-Norco (Riverside County; 54% Latino, 23% White, 11% Asian, 6% Black) also uses the Integrated Math curriculum and starts middle school in 7th grade. It offers the same two course compression sequences as Sacramento and Elk Grove. The one unique feature is that they offer an Integrated Math I Summer Bridge Course after 8th grade. This gives students a third point at which they can choose to accelerate in addition to those at 7th and 10th grades. See their Math Placement FAQ for details.

Garden Grove (Orange County; 53% Latino, 35% Asian, 7% White, 1% Black) uses the traditional curriculum and starts middle school in 7th grade. Their middle schools offer Algebra I in 7th grade and Geometry in 8th, which means that course differentiation must start earlier. I couldn’t find documentation of their elementary school math but I suspect it happens through their GATE program. Garden Grove has three elementary schools (e.g. this one) that cater specifically to GATE students. The course catalog doesn’t show any way for students to accelerate in middle school if they didn’t do so in elementary school.

Fresno (69% Latino, 11% Asian, 9% White, 8% Black) also uses the traditional curriculum and starts middle school in 7th grade. I couldn’t find a Math pathways document but I did find middle schools that offered Math 7 Accelerated followed by Algebra I in 8th grade.

Clovis (Fresno County; 39% Latino, 36% White, 15% Asian, 3% Black), also starts middle school in 7th grade but uses the Integrated curriculum. According to their course catalog, they offer Advanced Math 7 and Advanced Math 8 to cover three years of Math in two years. In high school, they offer both regular and Honors versions of Math 1, Math 2, and Math 3. Placement in Honors Math 2 requires both a good grade in Advanced Math 8 and a good score on a placement test. Honors Math 2 and Honors Math 3 compress three years of Math into two and prepare a student for Calculus.

Long Beach (LA County; 58% Latino, 13% White, 13% Black, 7% Asian) starts middle school in 6th grade and uses the Traditional curriculum. They offer Math 6 Accelerated and Math 7 Accelerated which combine three years of middle school math into two and enable a student to take Algebra I in 8th grade. A description of the eligibility criteria can be found here. Their high school course catalog has Accelerated Geometry, Accelerated Algebra 2 and Precalculus Honors courses but there doesn’t appear to be any pathway that gets a student to Calculus if Algebra I is taken in 9th grade.

San Bernardino (79% Latino, 11% Black, 5% White, 1% Asian) starts middle school in 6th grade and uses the Integrated curriculum. From their list of curriculum guides, it appears as if they offer no acceleration in middle school but in high school they offer Accelerated Integrated Mathematics I and II to compress three years of Math into two. Even if there are no accelerated classes in middle school, they do have a GATE program which offers “GATE cluster classes” that “differentiate content” in grades 4-8.

Santa Ana (Orange County; 96% Latino, 2% Asian, 1% White) starts middle school in 6th grade and uses the traditional curriculum. I couldn’t find a math pathways overview and the school websites are generally uninformative but I did find at least one middle school that offer Honors Algebra in 7th grade and Honors Geometry in 8th grade, which obviously requires that course differentiation happens even earlier. One high school course flow chart that I found gave no way for a student to accelerate once in high school. As an aside, the middle school that I linked to above is a “fundamental intermediate” school, which was a new concept to me. In a fundamental school such as MacArthur Fundamental Intermediate: "Primary emphasis is placed on a highly-structured program of basic academic skills and the establishment of good study habits. The school seeks to instill within each student a sense of respect, responsibility, patriotism, pride in accomplishment, and a positive self-image." It is fun to contemplate which would provoke the most controversy in San Francisco: offering Algebra and Geometry in middle school, emphasizing patriotism, or having a school named after Douglas MacArthur. Would you guess that Santa Ana is 96% Latino and has 81% of students eligible for free or reduced price meals? The desire for rigor and high standards is universal.

Oof. Just stumbled across this post while googling for info after our school district (Santa Clara USD) issued brand new pathways, and sure enough, there's the Algebra 2+Precalc/Trig compression in 10th grade. Options to accelerate to Algebra 1 in 7th grade are gone, but at least they allow Algebra 1 + Math 8 compression in 8th grade. I suspect your state survey is going to look very outdated by the end of this year.

How many (percent) students can pass Algebra? Is it required for graduation? I would guess some percent will never be able to pass.