The Edunomics lab at Georgetown University focuses on education finance nationwide. It’s sometimes nice to get a broader perspective. For example, this observation about education funding is very germane to what’s happening in San Francisco.

Adding staff is the big bet public education has pursued over the last 50 years…This has come at the expense of other investments: while school spending has risen, districts haven’t added more instructional time for students or raised teacher salaries.

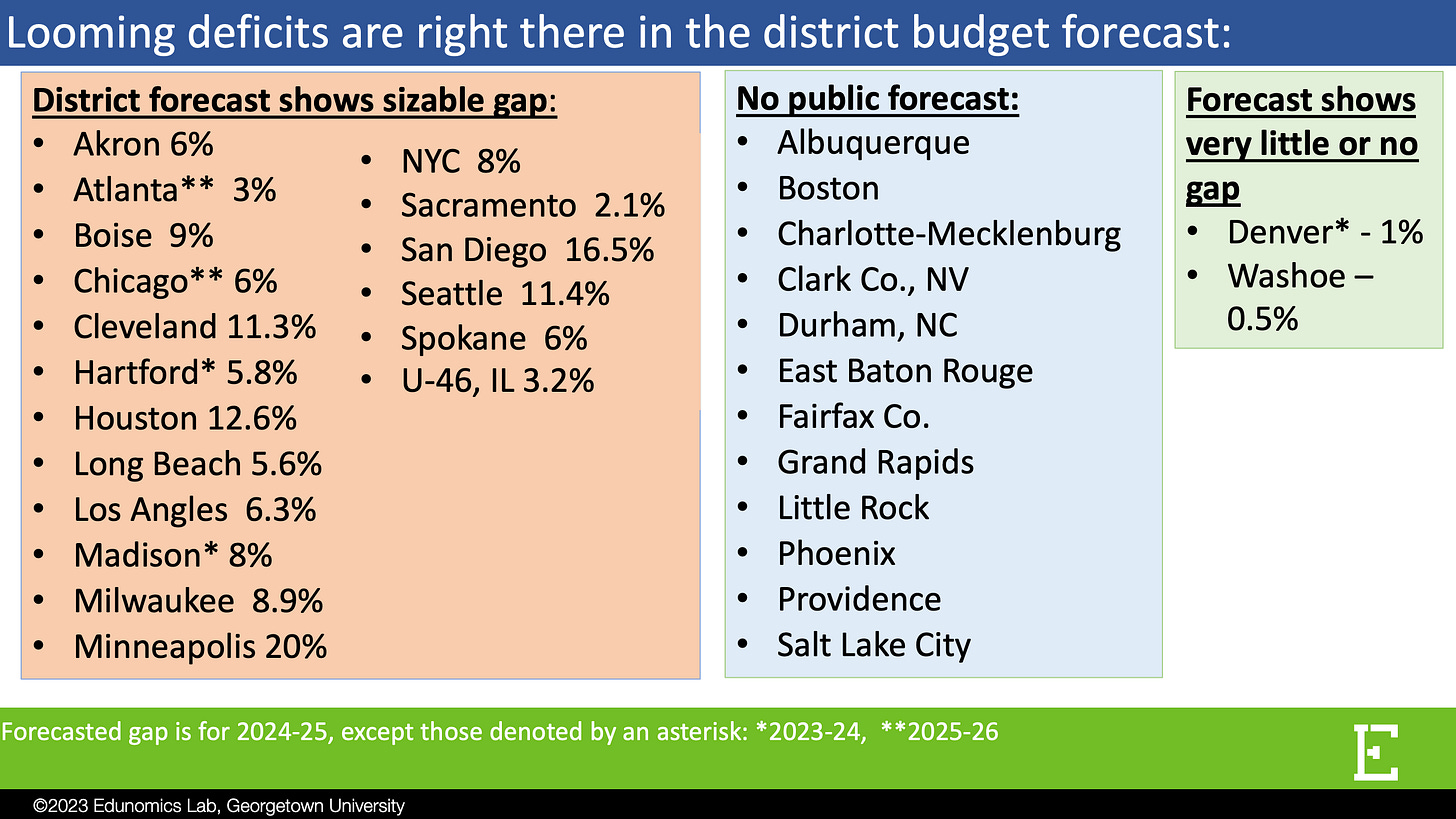

Their big focus at the moment is an impending fiscal crisis in many districts. Here’s a key slide from one of their recent webinars.

The district near us, SFUSD, will be hit by at least the first three of those shocks:

ESSER is the government’s pandemic-inspired boost to education funding. SFUSD used its ESSER funding to plug a structural deficit. When the ESSER funding goes away, the structural deficit will re-appear. As Warren Buffet likes to say: “only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked.”

Enrollment has declined nearly 10%, which will, after a lag, lead to a proportionate reduction in SFUSD’s funding from the state.

We don’t know what agreement the district and unions will eventually reach but it’s certain that the terms of any new contract will far exceed the “typical” numbers outlined above.

California may or may not enter a recession but it’s clear that the city of San Francisco is facing its own budget deficit and will have less money to bail out the district.

Were the district to accept the current proposals from the unions, the annual deficit in its unrestricted general fund would exceed 10% of revenues and its reserves would be totally expended in 2025-261. That wouldn’t be the highest deficit in the nation but it would be on the higher end:

Given the size of these deficits, Edunomics is forecasting a nationwide “bloodletting” in 2024-25 school district budgets.

SFUSD is aware that a deficit of this size is unsustainable. There’s a resolution on the agenda for the June 20 board meeting where the board:

“Commits to take action or actions to ensure that the school district meets the State minimum reserve for economic uncertainty and eliminates the school district's unrestricted general fund structural deficit in 2023-24, 2024-25 and 2025-26”

I don’t attend board meetings (or PTSA meetings or any other kind of meetings) but I did watch the recording of the June 6 board meeting2 during which the above resolution had its first reading. All of the commissioners who spoke acknowledged that there was work to be done but I’m not convinced that they realized how big a task they have before them. Closing a 10% gap is hard. Here are the options Edunomics laid out for closing a much smaller 4% deficit:

It is not easy for any district to take any of these steps at any time. SFUSD is under heightened public scrutiny since the events that led to the recall, has fragile relations with its staff thanks to the payroll debacle and ongoing salary negotiations, is led by a relatively new superintendent (one year on the job), and governed by a relatively inexperienced board (five of the seven members are in their first terms).

Last year, the board and district were able to agree some cuts (albeit under threat of a state takeover) and this was done with a minimum of public outcry. The next cuts won’t be so easy because every program will have its defenders.

Budget Review

Multi-Year Staffing and Budget Comparison

Every budget contains a comparison of the approved budget for the current year with the proposed budget for the upcoming year. This is useful but lacks a bit of perspective. I tried to do a multi-year comparison of the current budget with that for prior years but was stymied by a number of issues:

The district has a legal responsibility to ensure that restricted funds are spent on the purposes allowed by each fund source. If the district has discretion to pay for something out of restricted or unrestricted funds, it is sensible financial management to pay it out of restricted funds because that preserves financial flexibility. Something may thus be paid out of one fund in one year and a different fund in another year.

Staffing numbers are reported for school sites and for programs paid out of the unrestricted general fund but that leaves lots of gaps. Central office staff paid out of the restricted general fund or any of the other funds tend to be uncountable in the budget.

A cost may move between the district and the county office. For example, in some years the district gave more than $150 million from its general fund to the county office of education to pay for special education but, starting in 2022-23, special education is now paid directly from the district’s general fund and the county office’s entire budget is only $16 million. That’s a lot of money (and associated staff) to be moving around.

The 2023-24 budget contains exhibits that cover expenditures from “All Funds and Resources” (exhibits 9A, 9B). These are the most comprehensive general overview of the budget but they don’t exist for most earlier years.

Budget categories shift over time and it’s not always obvious whether a category was eliminated or merged.

The Board of Education document archives prior to 2018-19 don't include the actual budget books, only the resolutions to approve the budget books.

Instead of a comprehensive comparison, I’m therefore going to limit myself to a few observations, some specifically about the 2023-24 budget, some about how things have changed since 2018-19. If you’re interested in following along, the 2023-24 budget book is here and the 2018-19 one is here.

Special Education

The budgeted expenditures include a massive $230.7 million for special education (exhibit 9B) but there is no indication of where this money is spent and on what. $111.6 million (1,236 FTE) is for special education site staffing but the special ed site allocations according to the “weighted student formula and other site-based budget allocations” (exhibit 8a) sum to less than $1 million. There is no indication of how that money and staff is spread across the schools of the district. Presumably, these 1,236 FTEs are in addition to the 3,785 FTEs who are already in the budget for “TK-12 and County Schools”. Meanwhile, $75 million is for “special education general” but there’s no clue whether this is spent at central office or school sites and, if at central office, on what. How is anyone supposed to approve such an enormous black hole?

MTSS Site Allocations

SFUSD uses a “multi-tiered system of supports” (MTSS) to allocate additional resources to schools. In 2023-24, a total of 234.50 FTE will be provided by the MTSS, comprising a mix of assistant principals, instructional reform facilitators, literacy coaches, academic response to intervention facilitators, nurses, social workers, and counselors (exhibit 8B). In the 2018-19 budget, those job categories accounted for only 206 FTE.

Centrally-Managed Site Allocations

There are many other site FTE allocations that are centrally managed i.e. they are school staff but they don’t appear on the school site budgets. Curriculum and Instruction staff (with 2023-24 FTE in parentheses) include Arts & Music teachers (157.5), librarians (74.5), PE staff (47.8), career technical education (CTE) staff (16.4), multilingual pathways (9.1), ethnic studies staff (8.0), and computer science (0.6). That’s a total of 313.9 FTE (exhibit 8C), up from 253.4 in 2018-19, with all of the increase accounted for by more arts and music teachers. It is important to note that this does not mean that the district now employs more arts and music teachers than it did in 2018-19. It means that more of them are being paid by central office instead of out of school site budgets. The budgets do not enable anyone to know whether the district employs more, fewer, or the same number of arts and music teachers.

Curriculum & Instruction

The Curriculum & Instruction budget of $97.8 million covers 525.4 FTEs (exhibit 9B). 313.9 of those FTEs are the aforementioned staff who work at school sites but are managed out of central office (exhibit 8C). That means there are over 200 FTEs working at central office on Curriculum & Instruction. What are they doing?

LWEA/QTEA

$81 million of budgeted expenditures is on “LWEA/QTEA” (exhibit 9B). These are the acronyms for two propositions (Living Wages for Educators Act and Quality Teacher and Education Act) passed by San Francisco voters that bring in additional funds to the district. Classifying these additional funds as expenditures is odd because these propositions are more like a source of funds than an expenditure. I guess it was done this way as an accounting convenience because the proposition money is divided among people in every school and department but it’s still weird to see it as an expenditure line-item.

Custodial Services

The biggest non-school headcount item in the budget is custodial services. The 2023-24 recommended budget for custodial services is $48.4 million and that will pay for 388 FTE (exhibit 9a). That’s equivalent to $125,000 per FTE. This is a 0.6% increase in budget and a 3.4% increase in staff numbers from 2022-23. (exhibit 9B). Meanwhile, exhibit 6 shows that $32.1 million of this is coming from the unrestricted general fund and this will pay for 276.8 FTE. That’s about $116,000 per FTE. A little bit of middle-school algebra (sorry, high school algebra) shows that rest of the custodial services budget ($16.3 million; 111.2 FTE) works out at $147,000 per FTE. The high cost per FTE numbers doesn’t mean there is a cadre of highly paid custodians. It could be that the custodial services budget includes the cost of additional custodial services provided by outside companies (e.g. payments to Recology for trash removal) or the cost of supplies used by the custodians.

Now suppose we want to compare this to a few years earlier. The 2020-21 budget book shows a budget of $28.4 million for 249.3 FTE ($114,000 per FTE) in the unrestricted general fund. The 2018-19 budget book shows a budget of $28.9 million for 271 FTE ($107,000 per FTE) in the unrestricted general fund. Neither budget book gives a total (i.e. all funds) budget for custodial services so there is nothing to compare the full custodial services budget ($48.4 million; 388 FTE) to.

Transportation

The 2018-19 budget had a whole section about school bus transportation:

For the 2017‐18 school year, the Transportation Department provided school bus transportation services to about 1,500 students with Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) and 2,500 general education students. The total cost of transportation services has grown significantly over the past six years; in 2012‐13, SFUSD spent $22.3 million on transportation and in 2016‐17 it spent $31.68 million. For the 2018‐19 school year, the projected year end costs are $29.3 million. While costs are rising, the number of students receiving services is declining. Since 2012, the number of students with IEPs receiving transportation services has declined by about 150 students; SFUSD provided transportation services to about 1,616 students in 2012 and approximately 1,467 in 2017‐ 18. During the same time frame, the size of the fleet required to transport students with IEPs increased from 182 to 197 buses. A variety of factors have contributed to this significant increase in costs, for example, there is a greater array of school destinations because of SFUSD’s inclusionary practices, the number of students assigned to Non Public Schools has grown from 34 to 54, and the bell schedules have shifted significantly and become more complex as individual schools have changed their start and end times and added early release and late starts. In 2017‐18, there were 19 different start times and 27 end times (historically SFUSD had just 3 start times), and 10 schools had late starts and 43 schools had early release. There is a direct connection between the complexity of our bell schedules and the size of the transportation budget. For example, aligned early release could potentially save $2.73 million a year while also providing all schools with common planning time, and we could theoretically save an additional $2.08 million a year if we moved to three start times with an hour between times and clustered schools. Changing bell schedules is complex work that requires deep engagement with school communities and families. During the 2018‐19 school year, a cross departmental team … will focus efforts on aligning bell schedules and optimizing routes and schedules so that we can realize savings while strengthening services.

All the start times were indeed consolidated for the start of the 2021-22 school year (the “deep engagement with school communities and families” didn’t happen but the consolidation did). The budget for transportation in 2023-24 is $37.3 million (exhibit 9A). Or maybe it’s $36.9 million (exhibit 13). In either case, it’s up from $29.3 million in 2018-19. The budget is silent as to why the expected savings didn't happen, even though student numbers are down 10%.

Conclusion

The budget book does a good job of explaining certain features of the budget (e.g. MTSS, QTEA) and leaves other areas as complete blanks (e.g. special education). The district, for reasons that are sometimes good, occasionally moves expense items from one place in the budget to another or splits an item among multiple funds.

An unfortunate consequence of this budgetary sleight-of-hand is that it is difficult for even the most conscientious of school board members to know what the district is spending its money on and whether this is increasing or decreasing over time. This makes it hard for them to know what they’re approving and will make it challenging later this year when they have to find places to cut in the budget.

Housekeeping

This will be the last post until the next school year starts. See you all in August.

see slide 26 of this presentation

Yes, recordings of school board meetings are every bit as boring as you imagine them to be but at least you don’t have to sit through the whole interminable meeting.

Thanks again for all your hard work and analysis. I sure hope that the BoE is reading this.