Are small schools good for student learning?

No, but the middle school transition is bad for it

The Board of Education held a workshop a few weeks ago on Resource Alignment. The accompanying presentation was long and contained a lot of data but this slide caught many peoples’ eyes:

This slide drew a lot of flak because the district is pushing to consolidate schools in response to declining enrollment and one of the main arguments of opponents is that students do better in smaller schools and that any consolidations will thus hurt students.

This post will examine whether the criticisms of the slide are valid and dig in to the link between school size and student achievement.

School Size and Achievement

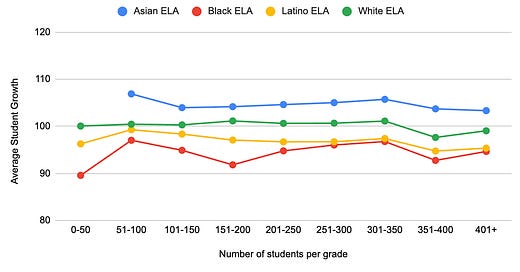

To begin, here’s my version of the district’s slide. It’s not completely identical - I’m including K-8 schools and we seem to be using slightly different enrollment data - but it’s basically the same.

The issue that occurred to me when I saw this presentation was this: In San Francisco, Asian and White students attend larger schools on average than Latino and Black students do. If the higher achieving student groups are concentrated in larger schools, then larger schools will show higher achievement levels. That could explain why the trend line in the chart shows a slight positive association between achievement levels and school size.

We can control for school composition by focusing on one particular student group at a time. Figure 2 shows how the achievement level of Latino students depends on the school size. The blue dots are the ELA results and the red dots are the Math results. There is still a very weak positive association between school size and student achievement. I produced similar charts for Asian students and for Black students and they showed the same thing.

Okay, you might say, small schools may not help all Latino or Asian or Black students but they may help the neediest among them. Here’s the same chart just for socio-economically disadvantaged (SED) Latino students.

It turns out that, at least in San Francisco, there is no evidence to support the idea that students do better in smaller elementary schools. Why might this be? One possibility is that it’s not because larger schools are inherently better; it’s because better schools get larger. If one school is better than another then more parents will choose to send their kids to the better school which will increase its enrollment and lower the enrollment of the poorer school. This process is facilitated in a district like San Francisco that has open enrollment.

Growth, not Achievement

Commissioner Matt Alexander had a different criticism of the district’s slide. He observed that the chart was focused on “proficiency rates rather than growth.[it] doesn’t show what schools are adding to the equation.” He’s correct. Here’s how the California Department of Education talks about growth:

Growth is different from achievement. Achievement—such as a single assessment score—shows us how much students know at the time of the assessment. Growth shows us how much students' scores grew from one grade level to the next. In an accountability system, aggregate student growth can provide a picture of average growth for students within a school, local educational agency, or student group.

California’s student-level growth model methodology uses statewide Smarter Balanced test results from students in grades four through eight. The first step in calculating student growth scores is to determine the student’s expected test score. The expected test score is determined by looking at students who had similar test scores in the previous grade and then evaluating their typical test scores in the current year. Once an expected test score is determined for each student, the difference between the student's expected test score and their actual test score is compared to arrive at their individual growth score. These individual scores are averaged for students at the district, school, and student group levels.

If you haven’t heard about these growth scores before, it’s because the first actionable set of growth scores won’t be published until after the 2024 SBAC results come out. Calculation of growth scores requires three consecutive years of data and SBAC scores are not available for 2020 or 2021 because of the pandemic. However, when the growth model was approved by the State Board of Education in 2021, they released results for 2018-19 for informational purposes in order to illustrate how the model works. For our purposes, it doesn’t matter that the data is now four years old. If school size has an effect on student achievement, then it will have an effect in every year. We should see that students in smaller schools exhibit greater growth than students in larger schools.

Here’s an example of how growth scores are calculated. The 50th percentile score for ELA in 3rd grade in 2017-18 was 2427 and the 90th percentile score was 2544. The 50th percentile score for ELA in 4th grade in 2018-19 was 2471 and the 90th percentile score was 2595. A student who scored 2427 in 3rd grade might be expected1 to gain 2471 - 2427 = 44 points in 4th grade. A student who scored 2544 in 3rd grade might be expected to gain 2595-2544 = 51 points in 4th grade. If both students actually gain 50 points, the first student has gained 6 points more than expected, for an individual growth score of 106, whereas the second student has gained one point less than expected, for an individual growth score of 99. Individual growth scores are volatile and not useful but, if you average the individual growth scores from enough students, you can start to make reasonable inferences about whether the students in a district, or a school, are learning more or less than would be expected and you can test whether student growth is affected by factors like, in our case, school size.

Growth scores are the only measure we have that adjusts for incoming student quality. We don’t have a measure for the quality of incoming kindergartners so the growth scores for elementary schools are based on how the 4th and 5th grade results compare to the previous year’s 3rd and 4th grade results for the same kids2. For middle schools, the starting point is each student’s 5th grade SBAC scores (over which the middle schools have no control). Measuring growth from this point can lead to some surprising results. A. P. Giannini is generally thought to be an excellent middle school and its growth scores in 2018-19 (108.1 for ELA; 110.2 for Math) bear this out. Everett is not so highly esteemed but its growth scores for 2018-19 (112.2 for ELA; 115.8 for Math) were even better3.

When people talk about small schools, it’s not always clear whether they mean a school with fewer pupils across all grades or a school with fewer pupils per grade. Is a K-5 school with 360 students (60 per grade) bigger or smaller than a K-6 school of 385 students (55 per grade)? I used the number of students per grade first and then looked at the effect of different grade spans.

Student Growth in Elementary Schools

Let’s focus initially on Latino students, the largest group in California schools. Figure 5 below shows growth scores for Latino students grouped by the size of school they attend. The yellow line shows the number of schools of each size (that have at least 11 Latino students). There are over 1500 elementary schools in the state with 51-75 students per grade, which is equivalent to a K-5 school size of 306-450 students. There are only 94 schools with 0-25 students per grade and 71 with more than 150 per grade (900 per K-5 school). The red and blue lines show the average growth scores of Latino students at those different size schools. They are flat lines: school size has no effect.

Let’s look at other groups. Figures 6 and 7 shows the growth scores for the four largest racial/ethnic groups. For both subjects, and every racial/ethnic group, it is clear that small schools are not associated with increased student growth in elementary school.

A couple of notes:

The scores for Asian students are at their highest, and for Black students are at their lowest, in schools of fewer than 25 students per grade. This is almost certainly an artifact of extremely small sample sizes. Growth scores are only calculated for groups of size 11 or higher. There aren’t many schools with fewer than 25 students per grade that have at least 11 Asian or Black students, the minimum to record growth scores for those groups. The datapoints shown here come from only 3 schools for Asian students and 20 schools for Black students (compared to 81 schools for the White student datapoint and 94 schools for the Latino student datapoint). In contrast, the datapoints in the 26-50 bucket come from 129 (Asian) and 145 (Black) schools so they’re much more reliable.

Black students seem to show improved growth as schools get larger. I suspect that school size by itself is not a factor at all in Black student growth (if it’s not a factor for other groups, why should it be a factor for Black students?) and that what we’re seeing here is that Black students do better in well-functioning schools and well-functioning schools tend to be larger. Whatever the explanation, there is certainly no evidence to support the notion that very small schools particularly help Black students.

Student Growth in Middle Schools

Figures 8 and 9 show the results for middle schools (defined here as schools that start in 6th or 7th grade and end in 8th grade). The story is the same: school size has no appreciable effect on student growth for any student group.

Grade Span Effect

School size may not affect student growth but grade span does. Some districts, like San Francisco, have the middle school transition in 6th grade so their elementary schools are K-5 and their middle schools are 6-8. In other districts, the middle school transition happens in 7th grade so their elementary schools are K-6 and their middle schools are 7-8. In addition, there are over 1,000 K-8 schools spread across the state. It turns out that average growth rates differ significantly depending on the grade span of the school. Figure 10 shows the average student growth by grade span of the school.

I’m just showing the numbers for Latino students in math but the story is the same for each racial/ethnic group and for ELA: K-6 schools do very slightly better than K-8 schools which do better than K-5 schools. There’s then a gap to grade 6-8 middle schools with 7-8 middle schools having the worst growth. There are nearly 350 grade 7-8 middle schools, and many more of the other types, so this is not a small data size issue.

Two things stand out:

districts whose middle school transition happens in 6th grade have lower scoring elementary schools but higher scoring middle schools than districts whose middle school transition happens in 7th grade.

students in K-8 schools show much higher growth than students in 6-8 and 7-8 middle schools.

This is all consistent with the idea that the disruption caused by the transition to middle school hurts student learning. Students who avoid that disruption by being in a K-8 school exhibit higher growth across grades 4-8.

Here’s a numbers-free explanation. Suppose that all districts are equally good no matter when their middle school transition is but that the transition itself hurts student learning. What would we expect to see? 4th and 5th grade students will exhibit the same growth in K-5, K-6, and K-8 schools. 6th grade students in K-6 schools will do much better than 6th grade students in 6-8 middle schools because they haven’t endured the disruption of the transition yet. This will raise the average growth score of K-6 schools above that of K-5 schools. In 7th grade, students in 7-8 middle schools will have their learning disrupted by the middle school transition whereas the students in 6-8 middle schools will be more adjusted to their new environments. 6-8 middle schools will thus show better growth than 7-8 middle schools. Meanwhile, students in K-8 schools, who have no middle school transition to endure, don’t have their learning disrupted and score higher than students in the 6-8 and 7-8 schools.

There’s more work to do here before I’d be entirely convinced of this explanation. Some K-8 schools have fairly even enrollment from grade to grade. Others add a lot of students at their district’s middle school transition point. If middle school transition is truly disruptive, schools that add students in 6th or 7th grade will show poorer growth numbers than schools that don’t. I’d also want to examine the districts that offer K-8 schools to see if there are other demographic or structural factors that could also explain the observed data.

Conclusions

Students in small schools do not learn more than students in large schools. There may be valid objections to what the district is proposing but this is not one of them.

If further work proves that K-8 schools deliver better results, SFUSD should consider reconfiguring more of its schools to this format.

It’s not quite as simple as I’m portraying here. The expected gain might be higher or lower than 44 points.

When growth scores start becoming a thing that districts and parents pay attention to, this will create some interesting incentives for elementary school principals. The optimal strategy will be to place the best teachers in 4th and 5th grades, because their work will determine the school’s overall score, and the worst teachers in 2nd and 3rd grade, because their ineffectiveness will not count towards the school’s score and may even help it by lowering the baseline for the 4th and 5th grade teachers.

Given the issues at Everett over the last few years, which have sometimes made the news, it’ll be interesting to see if its growth scores next year are as high.

So interesting. I think the 0-25 group is more nuanced. If the cut off for reporting is 11 students, in the smallest grade schools, you're potentially taking about a weighting towards schools that are majority a single race. So that begs questions like, who is in small, single race schools? How would you expect them to perform? One very big difference is that you're then likely talking about an immigrant population that potentially has more language focused needs to succeed vs. historically underprivileged community which maybe needs more resources to succeed. I don't think it's necessarily just sample size we're observing here, and there is danger to these communities if we don't stop and think about why, and how they might learn best. Anyway, I think it's important because we notice differences in performance. If these differences are brushed off, we might never ask the questions to help us understand why and what can be done about it.

I have been advocating for K-8 schools for years. Stable school communities are beneficial for kids, parents, and teachers and adding three extra years of community building is invaluable. Speaking from experience as a mother of six children who have attended either a k-5, k-8, and/or 6-8 I can attest to the total upheaval that transition is during a really emotionally intense time in a kids development. Im sure we can all agree, middle school is the armpit of education. For some reason someone thought it was a good idea to take a bunch or kids all going through the same hormonal upheaval and put them in the same building. And many of these kids are coming from smaller schools with teachers who have been with them for years, to giant middle schools where they feel nameless, faceless, overwhelmed, and isolated.