Introduction

The San Francisco Unified School District is presenting its budget at the June 6, 2023 board meeting. Additionally, the district is in negotiations with its various labor groups. They have been analyzing their enrollment, staffing, and salaries. They requested that I conduct an analysis that would compare SFUSD to other districts along the following dimensions:

staff to student ratios

the number of schools

salaries

the number of programs offered at schools

The district provided me a copy of the SABRE: Salary and Benefits Report, produced for SFUSD by School Services of California. They answered some questions I had, and gave me feedback on the organization of the first draft, but did not seek to influence or edit my analysis in any way. All conclusions are my own. All errors are my fault.

Methodology

Every school district files a Form J-90 ("Salary and Benefits Schedule for the Certificated Bargaining Unit"). This contains all the details about each district’s salary contract, including the full step-and-column schedules and details of how many are on each benefit plan. The CDE produces a database containing data from all the J-90s. I downloaded the database and used it to generate all the charts relating to staffing and salaries in this report. School Services of California uses the same data to produce the SABRE Report. I double-checked my calculated numbers (e.g. for average salary or benefit contributions) with those in the SABRE report to ensure they matched. I’ll sometimes use “teacher” as an umbrella term to cover everyone in the “certificated bargaining unit”. In San Francisco, that includes classroom teachers, teachers in admin roles, certificated pupil services staff, counselors, and librarians. It does not include nurses, social workers, paraprofessionals and other classified staff.

CDE also produces data on the enrollment in every school. This was the basis for the charts on school sizes.

All bar one of the charts shown here were are screenshots of Tableau vizzes. Clicking on the relevant links will open the vizzes and allow interactive exploration of the data. Gluttons for punishment can explore additional vizzes for which there wasn’t space in this report.

Background

A majority of school district funding is based on attendance. SFUSD’s attendance was essentially flat for the better part of a decade but, as figure 1 shows, attendance is down 10% since the last pre-pandemic year (2019-20). The impact of falling attendance has yet to be fully felt on the budget. Staffing has not adjusted at all to the lower attendance.

SFUSD’s 2nd Interim Financial Report this year said:

“Though our fiscal outlook through 2024-25 is positive, we continue to spend more funding than we generate through all state, federal, and local sources.”

Meanwhile, the district and union are renegotiating their contract. Although the district and union proposals are still far apart, any agreement will surely result in a significant salary increase.

Staffing

Figure 2 shows the number of certificated employees per thousand students for all districts. With 82 certificated staff per thousand students, San Francisco employs more than every district except Palo Alto and Sequoia UH (both 83).1

Notice in particular that San Francisco employs 40% more staff than San Mateo Union High (82 per thousand to 58 per thousand). Meanwhile, Oakland is higher than most at 70.

Number of Schools

To explore whether we have the right number of schools for our student population, we are going to focus on two numbers:

the average number of students per school

the percentage of schools in a district that are “small” i.e. the percentage whose enrollment is below a certain threshold.

Conceptually, the threshold is the minimum size necessary for a school to thrive. San Francisco has not conducted such an analysis so, for the charts, I’ve used thresholds calculated for Oakland Unified in 2019 (viz, 300 for elementary schools, 380 for middle schools, 500 for high schools). You can see the effect of changing the thresholds by opening them in Tableau. In general, the appropriate threshold will vary based on each district’s unique circumstances and aspirations. The more expensive a school is to operate, the more students the school needs, because student attendance is what brings in the money from the state. A district where salaries are low, building maintenance is cheap, average class sizes are large, and school staffing is bare-bones can afford to have smaller school sizes than a district where salaries are high, building maintenance is expensive, class sizes are small, and schools have a lot of ancillary support staff. Put another way, a district in an expensive city that wants to offer community schools with small class sizes taught by well-paid teachers can only afford to do so if it has fewer, larger schools.

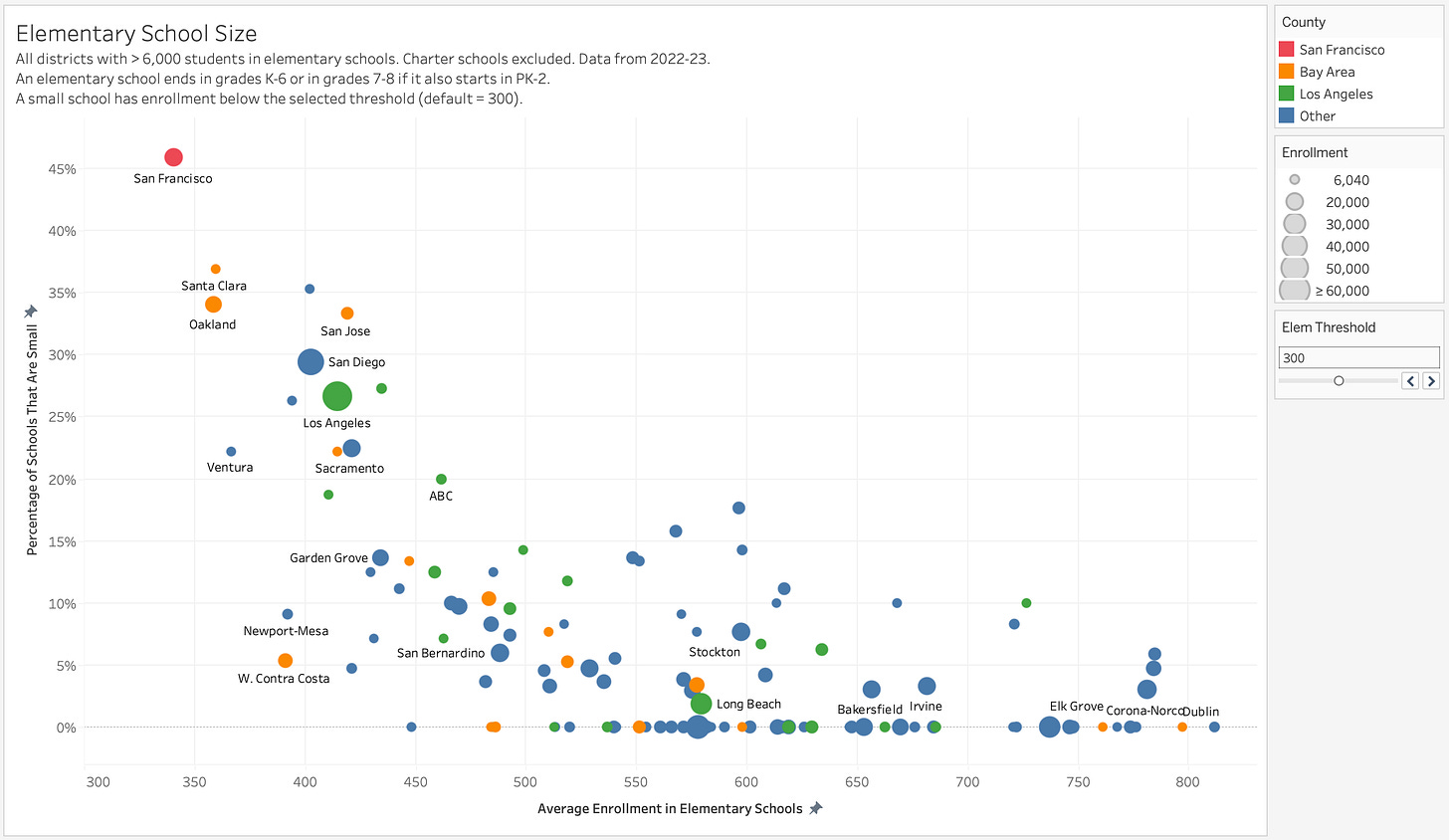

Elementary Schools

Figure 3 shows the average elementary school size and percentage of schools that are small in each district2.

San Francisco has the smallest elementary schools (average: 341) and the highest percentage of small schools (46%): 33 of 723 schools have fewer than 300 students.

The districts with the smallest schools tend to be large urban districts with shrinking student enrollment (e.g. LA, San Francisco, Oakland) or Basic Aid districts that have the money to fund smaller schools (e.g. Santa Clara). The districts that have average sizes greater than 550 include large urban districts (e.g. Long Beach), prosperous suburban districts (e.g. Dublin, Fremont, Irvine), and fast-growing inland districts (e.g. Corona-Norco, Bakersfield, Stockton). It is notable that districts that have experienced population growth in recent decades have chosen to construct larger schools even though their land values and construction costs are much lower than those in San Francisco.

Middle Schools

Figure 4 shows the data for middle school sizes.

San Francisco’s average middle school size of 661 is around the 10th smallest. Oakland’s are the smallest at 480. Only a dozen districts have any schools with fewer than 380 students. In some of the cases (e.g. Santa Clara and Sacramento), it’s just one small school. San Francisco has three small schools (Brown, Visitacion Valley, King) out of thirteen. Oakland has five out of eleven.

Since most districts have only a small numbers of middle schools, the choice of threshold can affect the results significantly. Three of West Contra Costa’s six middle schools have between 390 and 410 students so if the threshold were set at 410, West Contra Costa would appear above Oakland.

High Schools

Figure 5 below shows the data for high schools.

San Francisco’s average high school size is just over 1,000, the fourth lowest average. Five of fifteen high schools (Independence, Jordan, Academy, International, and Marshall) are under the 500-student threshold and another (O’Connell at 506) is just above it.

Oakland has both the smallest average high school size and a high percentage of small schools (6 of 13). Los Angeles (33 of 114) and San Diego (6 of 22) are closer to San Francisco. Most of the other districts that have small high schools have exactly one (e.g. Kern High 1 of 19, East Side Union High 1 of 12, Sacramento 1 of 9, San Jose 1 of 7, West Contra Costa 1 of 7, Mt. Diablo 1 of 6, Fremont 1 of 6, Sequoia Union High 1 of 5, Tamalpais Union High 1 of 4, Paramount 1 of 2).

Compensation

Compensation has multiple components: salary, bonuses, and benefits. Let’s consider each in turn.

Average Salary

As figure 6 shows, San Francisco’s average salary is lower than the average across all districts in the state4 and lower than in most other Bay Area districts.

Notice that San Mateo Union High’s average salary is nearly $40,000 more than in San Francisco and Oakland’s average salary is $14,000 less. It’s easy to see why staff in San Francisco might eye those in San Mateo enviously.

Early Career Teachers

Part of the reason San Francisco’s average salary is so low is that a much higher proportion of the staff is early career.

All school districts use column and step salary schedules. Your column is determined by your education level (e.g. BA, BA+30, BA+60, where the number refers to additional credits) and your credential status (whether you have yet obtained your full teaching credential). There is no standard set of columns. Less than 20% of districts have separate intern/emergency or non-credentialled columns. Many districts have more than three columns based on education. You’ll often find some or all of BA+15, BA+45, BA+75, BA+90. Your years of experience determine your step.

Figure 7 shows the number of FTEs on each step in San Francisco. The colors refer to “columns” in the salary schedule.

The step on the salary schedule is a rough proxy for experience. San Francisco doesn’t have over 200 people in the BA+60 column with exactly 28 years of experience. The schedule doesn’t extend beyond 28 steps so everyone with at least 28 years of experience remains on the 28th step. Similarly, the BA+30 column ends at step 15 so anyone with 15 or more years of experience stays on step 15. For a sense of scale, in San Francisco, step 1 on the BA+60 column pays 27% more than step 1 on the BA (Intern/Emerg) column and step 28 on the BA+60 column pays 60% more than step 1 on the BA+60 column.

Figure 7 showed that San Francisco has a lot of staff on steps 1-5. Figure 8, below, shows the percentage of staff in each district that are on steps 1-5 and the average salary of those early career teachers.

31% of SFUSD’s staff are on steps 1-5. Among Bay Area districts, only Oakland has more.

An obvious hypothesis is that districts that offer higher salaries have less staff turnover and therefore need to recruit fewer early career staff. There is some evidence to support this: the four districts in the top left offer the highest salaries and have low numbers of early career staff. There are also a bunch of districts in Alameda that have fewer early career staff and higher salaries than San Francisco. But there are also plenty of Bay Area districts (e.g. South San Francisco and Mt. Diablo and Berkeley) that have far fewer early career staff than San Francisco despite salaries that are similar to, or lower than, San Francisco’s. Salary is an important factor in staff retention but it’s not the only factor.

Bonuses

Just looking at average salaries in 2021-22 is a bit unfair to SFUSD. That year, SFUSD paid a one-time $4,000 bonus to all employees while the district and union were gearing up for the ongoing contract negotiation. Even in normal years, SFUSD pays a series of bonuses to qualified employees. In 2021-22:

347 received a $5,000 bonus for National Teacher Certification.

109 received a $3,000 8-year retention bonus.

241 received $2,500 4-year retention bonus.

717 received a $2,000 bonus for being in “high potential schools”

1,100 received a $1,000 special education bonus.

All of those bonuses together added $5,423 to the average cash compensation per teacher. This brought the average cash compensation to over $90,000 rather than below $85,000. The only Bay Area district to pay more in bonuses than San Francisco was Oakland, which was also gearing up for its own contract negotiation.

Employee Benefits

Benefits packages are notoriously difficult to compare. Districts offer health plans from multiple insurers. Some plans are more generous than others and have higher or lower copays. A similar plan from the same insurer (e.g. Kaiser) might cost more in one location than another. Even if two neighboring districts offer exactly the same plan from the same insurer, they may differ in the fraction of the total premium that the district pays. Even if two districts offer exactly the same plans at the same prices to their members, the employees in one district might prefer a HMO-type plan while employees in the other district might prefer a PPO-type plan. Even if everyone wants a HMO plan, one district may have more unmarried employees and the other more who have families. Even if the mix of single and married employees is the same, the married employees in one district might be more likely to enroll in their spouses’ employers’ plans if the district’s plans are not competitive in the local context.

The SABER report ignores these complexities and compares benefit packages by looking at the average amount that the district contributes to the cost of employee benefits per enrollee. Figure 9 is a histogram of average district contribution to health care costs per enrollee.

The outliers on the left, many of which are in Alameda, contribute very little to the cost of plans. In Hayward, the “district only contributes to dental and vision”. In Fremont, the district pays only $1,752 of the cost of each health plan, whether it’s a single-person plan, two-person plan, or family plan.

SFUSD’s average contribution to employee benefits ($10,332) is lower than most other districts for two related reasons:

it contributes less than other districts to the cost of family plans;

most of the employees it does cover are on single person plans rather than two-person or family plans.

Most Bay Area districts offer one or more healthcare plans from Kaiser. SFUSD’s most popular plan is one from Kaiser. San Mateo UH also offers a Kaiser HMO plan. The annual cost for an active employee is slightly higher in San Francisco ($8,190 vs $8,079 for a single employee; $23,111 vs $22,138 for a family), indicating that the plans probably provide similar benefits. Both districts cover 100% of that cost for single employees. But San Mateo UH also covers 100% of the cost for families while SFUSD only pays $12,674.

Looking around the Bay Area, there are other districts like San Mateo UH that pay 100% of the family cost (e.g. Oakland, San Ramon Valley, and Sequoia UH) and still others that pay less than 100% but more than $20,000 of the cost (e.g. Mt. Diablo, West Contra Costa, Palo Alto). Equally, there are districts that contribute less to the cost of a Kaiser family plan than San Francisco does. Some of them are regular districts (e.g. Alameda, Livermore Valley, Dublin, Walnut Creek) and some of them are wealthy Basic Aid5 districts (e.g. Las Lomitas Elementary in Menlo Park, Portola Valley Elementary, Woodside Elementary). If there’s a pattern in which are generous and which are not, it’s not obvious to me.

Of SFUSD employees who sign up for one of the health care plans, 76% opt for single person plans. That’s less than the 87% of enrollees who are on single-person plans at San Mateo-Foster City Elementary but it’s far higher than the 36%-55% who are on single person plans at all the other Bay Area districts with at least 500 employees on health plans (viz. Oakland, Antioch, Mt. Diablo, Pittsburg, West Contra Costa, San Ramon Valley, San Mateo UH, Sequoia UH, East Side UH, Palo Alto, and San Jose). That may mean that SFUSD has an uncommonly high number of unmarried employees6. Or it may mean that many married SFUSD employees opt for SFUSD’s 100% paid single person plan and enroll their families in their spouses’ employers’ plans.

Retiree Benefits

Every teacher is entitled to a pension based on age at retirement and number of years of service. To fund those pensions, teachers and school districts have to contribute a percentage of payroll to CalSTRS. Because the pensions were historically underfunded, the required contribution rate for districts has been increasing in recent years and was 19.1% in 2022-23. That’s a very substantial expense for districts, which has limited their ability to raise salaries, but it is ignored in the J-90 data, presumably because the same pension rules apply to all districts.

What is not the same for all districts are Other Post-Employment Benefits (OPEB, for short). Teachers can retire at 55 but the median age at retirement is 62.4. In the days before the Affordable Care Act, it could be difficult for retirees who were not old enough for Medicare to obtain health insurance. Many districts therefore extended benefits to members who had retired but not yet reached 65.

Of the 208 districts with at least 6,000 students, 85% provide at least some benefits to retirees under 65. Some enable those retirees to continue their enrollment in their health plans but without paying any of the cost (similar to how COBRA works in the private sector). Other districts pay some, or all, of the cost of the retiree health plans.

SFUSD does not contribute to retirees’ dental and vision plans but does contribute to the healthcare plans. Health plans for these retirees are more expensive than for regular members. SFUSD covers 100% of the $16,441 cost for a single-person Kaiser plan and $20,518 of the $24,595 cost of a two-member plan (few retirees have kids young enough to be eligible for family plans). Of the districts that were more generous than SFUSD for employee benefits, only Palo Alto is as generous for retirees under 65. Oakland and San Mateo UH don’t provide retiree benefits at all; Mt. Diablo provides dental and vision benefits only; San Ramon Valley, Sequoia UH, and West Contra Costa contribute some or all of the cost of their healthcare plans but those plans are much cheaper than San Francisco’s, indicating that the plans must be less generous. Sequoia contributes 100% of the $9,220 cost of its plan while San Ramon Valley contributes $3,648 to the $12,540 cost of its plan.

Most districts stop paying for retiree benefits when the retirees are eligible for Medicare. Some continue providing the benefits until age 70. But 15% of the districts with more than 6,000 students (and 12 of the largest 50 districts) provide benefits for life. San Francisco is one of those districts. It again pays 100% of the premium for a single-person plan. Fortunately, those premiums are lower for this group of retirees. The single-person Kaiser plan costs only $4,252.

Figure 10 is a histogram of retiree healthcare enrollment. It shows the number of retirees aged over 65 receiving healthcare benefits from a district as a percentage of the number of FTEs currently employed.

The majority of districts provide benefits to zero retirees over 65. Uniquely among districts, San Francisco provides benefits to more retirees over 65 than it has current employees (4,513 vs. 3,652).

SFUSD spends more on benefit plans for retirees ($35.3 million, or $790 per student) than for current employees ($32.5 million). If SFUSD were magically free of the obligation to pay for retiree health care, it could afford to spend over $9,500 extra on compensation to each of its current employees.

OPEB liability

Historically, San Francisco and many other districts would simply pay those retiree health premiums every year. This pay-as-you-go method keeps the current cost down but ignores the future. A promise to pay someone’s health care premiums decades from now is the same as a promise to pay that person a pension decades from now: in accounting terms, it is a liability. While districts are required to set aside money today to fund future pension promises, they are not legally required to set aside money today to fund their OPEB liability. They are supposed to conduct periodic actuarial valuations to know how big their liability is but funding that liability is an issue of responsible financial management rather than legal obligation. SFUSD has lately been attempting to be responsible but it has a big hole to dig out of. In June 2022, an actuarial valuation put SFUSD’s unfunded liability at $1,039 million (liability of $1,071 million less funding of a mere $32 million). For budget year 2022-23, OPEB benefits (i.e. the district’s contributions to retiree benefits) were expected to cost $34 million but funding of the huge liability required an additional contribution of $45 million which is about $1,000 per student (Source: page 22 of this).

It’s hard to compare OPEB liabilities across districts because of reporting inconsistencies. SFUSD doesn’t report its own OPEB liability on its J-90 report. Those districts that do report their OPEB liabilities on their J-90 reports use a variety of valuation dates and the underlying actuarial valuations may make different assumptions about investment growth, healthcare cost growth, longevity trends etc. Liabilities can be very sensitive to those assumptions so one district’s reported liability may or may not be directly comparable to another’s. With that enormous caveat in mind, SFUSD’s liability per student ($23,240) is the second-largest among all districts, trailing only Los Angeles. (SFUSD has more retirees per student than LA and contributes more per retiree than LA so I suspect that LA’s higher liability is due to the two districts’ actuaries making different assumptions). Only five other districts have a liability per student greater than $10,000. I’m not going to draw a chart for this one because a pretty picture would give an illusory impression of the quality of the underlying data.

Funding the OPEB liability is absolutely the right thing to do but we should recognize that there is a generational injustice. Today’s students are essentially paying three sets of healthcare premiums:

this year’s healthcare for their current teachers ($32.5 million);

this year’s healthcare for retired teachers ($35 million);

future healthcare for retired teachers ($45 million).

The students of earlier generations got a free ride by getting an education without paying for all the promises made to their teachers. Today’s students are picking up the bill.

Staff Compensation per Student

School districts exist to educate students and much of their revenue is based on the number of students they’re teaching. We can integrate all the salary, benefits, and staffing data by looking at compensation on a per student basis.

Figure 11 is a histogram showing the non-pension compensation to certificated staff per student in California school districts. For the student count, I’m using average daily attendance (ADA) rather than enrollment because districts get paid for attendance, not enrollment.

San Francisco spends more on teacher compensation than every district in the state, bar three basic aid districts on the peninsula: Palo Alto, Sequoia Union High, and Santa Clara. How can this be? San Francisco spends more on teacher compensation than San Mateo Union High, even though average salaries are nearly $40,000 higher in San Mateo UH because:

San Francisco employs 40% more teachers

San Francisco is still paying for retired teachers whereas San Mateo is not.

Number of Programs

I was not able to find good comparative information is on the number of programs offered at each school. It is generally believed that SFUSD offers, for example, more language programs than most other districts but there is no central database with such information.

As mentioned earlier, counselors and librarians are part of the certificated bargaining unit in San Francisco but nurses and psychologists are not. This is not a universal practice. Among all districts with average daily attendance over 6,000, 54% include nurses, 50% include librarians, 41% include counselors, and 11% include psychologists, in their certificated bargaining units. Ideally, we’d adjust each district’s FTE count to exclude these groups because that would give us a standard base for comparison but we can’t because we don’t know how many are in each group.

For simplicity of calculation, I set the enrollment limit at 6,000 for elementary schools, 2,500 for middle schools, and 4,000 for high schools. I was shooting for a cut-off of 1,000 kids per grade but a complicating factor is that middle school is grades 6-8 in some districts and 7-8 in others.

It’s 72 schools because I’m including the eight K-8 schools as elementary schools and excluding all the early education schools that offer transitional kindergarten. Excluding the K-8 schools from the calculation would lower SFUSD’s average size to 317 and increase the percentage of small schools to 50%. Among districts too small to go on the graph, there are a few that have a smaller average size than San Francisco, most notably Jefferson Elementary in San Mateo (304) and Berkeley (323).

I admit 6,000 is a bit of an odd cut-off. I started with 10,000 but discovered that excluded most districts in San Mateo which are very relevant in any discussion about salaries because those are the districts with which SFUSD competes for staff. Making the cut-off much lower than 6,000 would add so many datapoints that it would make some of the graphs less legible.

A basic aid district is one whose income from property tax exceeds what it would be entitled to under the state’s Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). Basic aid districts don’t receive any LCFF money but they may receive funds under other smaller state funding programs. That’s the “basic aid” bit. Many districts in Marin, San Mateo, and Santa Clara are basic aid but not all. In San Mateo, Belmont-Redwood Shores, Brisbane, Hillsborough, San Mateo-Foster City and South San Francisco are basic aid but Burlingame, Millbrae and San Carlos are not.

It almost certainly does: cities attract unmarried people, some of whom then move to the suburbs when they get married and have kids.

@cheesemonkeySF

Ideally, I'd restrict the comparison to large unified districts that are near SF but that would mean ignoring most of the districts in San Mateo which may not be comparable as districts but are very real alternatives for teachers (like you). You are absolutely right that high school districts on average pay more than unified school districts. In fact, in the Bay Area, elementary school districts also pay a bit more than unified districts. (simple unweighted means - I haven't checked whether still true when weighted by student numbers). This is driven in part by having more money per student and in part by requiring fewer staff per student. Palo Alto and Santa Clara are two unified districts that are in the fortunate position of having so much money that they can pay high salaries and have high staff numbers.

My point in emphasizing the San Mateo Union High comparison was not to say that SFUSD could or should match it on staff numbers or salary but to emphasize that there is a very real trade-off between the two that results in huge differences in salary. Given the amount SFUSD spends on compensation, it could pay much higher salaries at the cost of reduced staff numbers. SFUSD has, consciously or unconsciously, and with the acquiescence of UESF along the way, chosen to be a high staff low salary district. When you have a lot of (cheaper) early career staff, student achievement is surely affected, partly because early career staff may be less effective and partly because a chunk of your more experienced and higher paid staff are needed to mentor and supplement the junior staff.

Long Beach has about 15% early career staff (to SFUSD's 31%) and the early career staff earn almost exactly the same as SFUSD's. Of course, retention may be affected by what your future earning prospects are more than by what you're currently earning and Long Beach does pay more to more senior staff.

Excellent analysis. Thank you for doing this!

One thing this got me thinking about: when I taught in OUSD, I taught at a small school (about 300 students) in the flatlands. We felt incredibly understaffed, given the needs we had — and this contributed to me burning out and eventually leaving the classroom. Of course when schools are too small, they are much more likely to feel understaffed — which I imagine contributes to turnover. Another negative feature of small schools, unfortunately.