I’ve been digging in to the material from recent board meetings and had intended doing a single omnibus post about the things that most caught my eye. The draft was getting far too long so I’ve decided to break it into three separate posts, which will be hitting your inboxes over the next few days. Here’s the first, which draws on the Audited Financial Report for 2023-24.

Open-Ended Promises Are Expensive

Every school district offers pensions to its retirees. Every school district offers healthcare benefits to its employees. SFUSD goes beyond that and provides medical benefits to retirees for life. Only a fraction of districts provide any benefits to retirees; most of those that do terminate coverage at some age. San Francisco is one of the few that provide coverage for life.

This arrangement suited everyone for years. The promise of lifetime healthcare coverage was attractive to long-term employees and made up somewhat for the lower salaries the district offered. Promising lifetime healthcare coverage suited the district too because it cost them nothing. A prudent well-managed district would have set aside money to pay for the promises being made to all those employees. Well, a prudent well-managed district wouldn’t have made those promises in the first place but, if it did, it would have set aside money to pay for them. San Francisco just kept writing blank checks. It adopted a pay-as-you-go approach. It paid the required contributions for all current retirees and just assumed that it could keep doing that indefinitely.

Changes in accounting rules forced a change in behavior. The principle now is that if you make a contractual promise today (“if you work for us for twenty years, we’ll provide lifetime healthcare benefits”), you have to set aside enough money today to pay for that promise. The accounting term for these retiree healthcare benefits is Other Post-Employment Benefits (OPEB). Districts are now supposed to set aside money in a fund to pay their OPEB promises and they have to quantify the extent to which their OPEB promises are unfunded and show that as a liability on their balance sheets. The key term is unfunded. Being obliged to pay future healthcare premiums is fine provided you have set aside enough money to pay for them. Only in recent years has the district started doing that.

Valuing the cost of lifetime promises is complex so the district hires an actuarial firm to provide periodic valuations. Here, roughly, is how OPEB liability is quantified.

The actuarial firm projects how much the district is going to have to spend on retiree healthcare over the next decades. That calculation depends on how many retirees there are (now and in the future), how many avail of the benefit, how long they live, and how much healthcare costs change in the future. This in turn is partially dependent on inflation.

The value of this liability is calculated by discounting those future payments back to today using some discount rate.

The district continues to pay the medical premiums for all the current retirees.

The district pays some additional money into a trust fund that will be invested in the hope that it will grow to pay future medical premiums

The actuarial firm also calculates whether the money the district has set aside in the trust will be sufficient to make those future payments. To do that, it makes some assumptions about how much the district’s trust fund will earn on its investments.

The difference between the value of the projected future medical premiums and the projected value of the trust fund is the district’s unfunded OPEB liability.

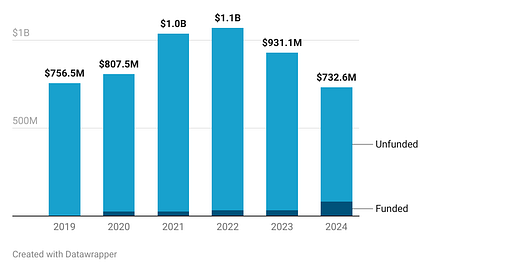

Back in June 2022, the district’s total OPEB liability reached $1,071 million of which only $32m was funded, leaving an unfunded liability of $1,039 million. By June 2024, just two years later, the unfunded liability had shrunk to “just” $649 million, an improvement of $390 million.

The district’s future obligations didn’t change. What changed is the discount rate used to value those future obligations. The 2022 audit used a discount rate of 2.81%, the 2023 audit used 4.1%, and the 2024 audit used 5.4%. Discount rates are supposed to be based on an index of 20-year municipal bond rates and interest rates did rise over this period but the size of this increase was surprising to me1.

Even though the unfunded OPEB liability has shrunk significantly, it’s still bigger than SFUSD’s unfunded pension liability2. Moreover, since other districts don’t share SFUSD’s OPEB problems, the state is not going to bail the district out in the same way that it does with pensions. The OPEB liability is entirely SFUSD’s problem and the district has only just started to set aside money to address it. It set aside $25m in fiscal year 2020, zero the next two years, $5m in fiscal year 2023, and $50m in fiscal year 2024. That’s in addition to the $34 million cost of healthcare premiums for current retirees. An extra $50 million would ease the district’s current budget crisis. To be clear, my complaint is not that the district set aside $50 million, it’s that prior executive teams and boards of education allowed the situation to fester for so long that setting aside $50 million was necessary.

You can think of it as intergenerational theft. Yesterday’s students didn’t set aside enough money to pay for their teachers’ retirement healthcare benefits so today’s students have to pay for both today’s teachers and yesterday’s. This intergenerational theft is going to continue for decades until the OPEB liability is fully funded.

That makes it all the more important that the district not compound its prior mistakes. It can’t legally renege on contractual promises it made decades ago but it can stop making those promises. The district is embarking on a renegotiation of its existing contracts with its unions. Ending lifetime medical benefits should be near the top of its list of requests. New hires should be paid higher salaries in compensation for not having the possibility of earning lifetime healthcare benefits.

The precise index that the actuaries reference is not available online but the closest I could find (the S&P municipal bond 20-year high grade rate index) never reached 5.4%.

There’s a good argument that the pension liability is understated, as it is for most public sector pensions. The accounting rules that govern public sector pensions (but not private sector pensions) say they should use the return they hope to make on their investments as the discount rate used to value their pension obligations. This is economically dubious practice because the pension obligation is certain but the investment return is not. The pension obligation should use a much lower discount rate which would drive up its valuation. It also provides a perverse incentive to invest in ever-riskier assets: the riskier the investments, the higher the expected return; the higher the expected return, the higher the discount rate; the higher the discount rate, the lower the pension liability appears to be. This article from Stanford gives the overall argument in more detail. This NY Times story about CalPERS deals with the perverse incentive. SFUSD’s main pension is with CalSTRS, not CalPERS, but the incentive is the same.

Doesn’t CalSTers offer healthcare to retirees? Why does SFUSD offer duplicative benefits?

With respect to your second footnote....

There’s a better argument that includes "the purpose of the measurement." The choice of discount rate should align with why the liability is being measured in the first place.

For example:

For plan funding purposes, like those governed by GASB for public plans or ERISA for private plans, the goal is to assess long-term sustainability based on the plan’s ongoing investment strategy. In this context, using the expected return on assets is consistent with the plan’s ability to invest over decades and meet obligations as they come due.

For plan termination purposes, such as in the case of private-sector plans being shut down and liabilities transferred to an insurer, a risk-free discount rate is appropriate—because the obligation becomes immediate and must be backed by secure, guaranteed assets.

Applying a risk-free rate universally, as some critics argue, may be theoretically appealing but practically misleading. It assumes an immediate wind-up scenario, which is not the case for ongoing pension plans. These plans have taxing authorities behind them, long investment horizons, and stable benefit payout patterns.

So while it's true that using higher expected returns lowers reported liabilities, it's not necessarily a perverse incentive—it’s a reflection of the economic reality under which these plans are designed to operate.