SFUSD's Per-Pupil Expenditures Try to Hide the Cost of Small Schools

Is SFUSD not able to account for half its expenditures or does it not want to?

Per-Pupil Expenditures

The Every Student Succeeds Act, signed by President Obama in 2015, introduced a requirement that all school districts throughout the country report actual per-pupil expenditures (PPE) at the individual school level. The details of how that was to be done were left to the individual states. In August 2018, four and a half years ago, the CDE defined what is supposed to be included in the calculation:

“all LEA (Local Education Agencies such as school districts) expenditures that represent the ongoing, day-to-day operations of schools and LEAs for public elementary and secondary education, i.e., current expenditures, should be included in the calculation. These include, but are not limited to, instruction, instructional support, student support services, pupil transportation services, plant maintenance and operations, and general administration.”

The only expenditures to be excluded “are either not associated with prekindergarten through grade twelve students, such as adult education; or are one-time, significant outlays that may distort the data, such as facilities acquisition.”

At the school level, “the per-pupil expenditure calculation will include expenditures charged directly to a school plus the school’s share of expenditures that are charged centrally at the LEA level but that benefit the schools, i.e., central expenditures. Central office costs are supposed to be allocated to school sites using a reasonable allocation methodology such as per student or per staff or per square foot or per school. The appropriate methodology would depend on the cost. HR costs might be allocated on a per staff basis; insurance on a per square foot basis; assistant superintendents on a per school basis; and IT on a per student basis.

One of the motivations for the new reporting requirements was the belief that districts often under-funded the neediest schools, whether intentionally or not. For example, teachers in needy schools might have less experience than teachers elsewhere in the district. Even though the pay scale is the same across the district, teachers with more experience earn more money so schools with longer tenured teachers might end up having more money spent at them. To make such issues visible, districts were instructed to ensure that “school-level expenditures reflect costs that were actually incurred at the school site…LEAs should not simply use an averaging methodology to distribute all expenditures among all of their schools”.

Districts were also instructed that “all of an LEA’s funds in which its day-to-day operations are reported should be included”. Depending on the mix of funds and the type of expenses, the amount to be allocated might even exceed the total general fund expenditures.

In short, the per pupil expenditure report is supposed to allocate virtually all the day-to-day expenditures of the school district among each of its schools. This information would then provide a concrete basis for informed debate about the appropriate distribution of spending among schools.

The first PPE reports were produced for the 2018-19 school year and the most recently published ones are for the 2020-21 school year. The published reports don’t include a lot of detail. At the district level, all that’s published are two numbers, an amount per student from federal sources and an amount per student from state and local sources. At the individual school level, the reports further distinguish between school expenditures (think school site budgets) and central expenditures (i.e. amounts spent by the district office for the benefit of the school).

Why can’t SFUSD account for half its spending?

If a district is doing a good job at calculating its PPE numbers, the sum of these amounts multiplied by the district’s enrollment should come close to the district’s total general fund expenditures. For example, Long Beach reports spending $1,972 per pupil from federal sources and $11,169 per student from state and local sources. That’s a total of $13,141. Long Beach had 71353 students so this represents expenditure of $938 million which is 101% of Long Beach’s general fund expenditures1 for the year. Presumably it’s more than 100% because they included expenditures from other funds apart from the general fund. Superintendent Matt Wayne’s former district, Hayward, reported $2,642 per pupil from federal sources and $13,459 from state and local sources. It had 19,633 students so this represents $316 million in expenditure which is 105% of Hayward’s general fund expenditures for the year. As the histogram in figure 1 shows, most districts were able to allocate around 100% of their general fund expenditures.

Now, let’s look at San Francisco Unified. It reported $999 per student in expenditure from federal sources and $7032 expenditure from state and local sources. It had 531342 students so this accounts for only $427 million in expenditure which is just 47% of SFUSD’s general fund expenditures for the year. The most charitable interpretation I can give to this is that SFUSD is just lazy. They assume no one at CDE will push them to produce a more complete analysis so they go with something that’s easy to produce even if it excludes more than half of spending.

A less charitable interpretation would be that they don’t want to have to defend the numbers that would show up if they did a proper attribution. Around about 2016-17, SFUSD made a dramatic change in teacher assignments: many teachers who were previously assigned to school sites were moved to the central office. A music teacher who might previously have been assigned to spend 20% of her time at each of five schools was now assigned 100% to the district office. Before SFUSD made this change, fewer than 10% of FTEs were employed out of the district office. After the change, over 30% of FTEs were employed out of the district office. Only one other district (viz, Pomona) comes close to this number. Most are well under 10%. Where those centrally-employed employees actually spend their time is now completely invisible in the public class and course assignment records. I believe one of the justifications for this change was precisely that the site budgets for some schools could not pay for some personnel that the district (and board) thought they should have. Instead of modifying the school site budgets to give an increase to these schools (which would have been a very visible act that might have provoked debate), they decided to bring all those personnel into the central office so that they could continue to provide the services without actually having to charge the school budgets for them. The whole purpose, in other words, was to obscure the costs.

Central Expenditures

We can observe this cost obfuscation by looking at what happens when central expenditures do get allocated. Recall that these are expenditures paid centrally by the district but which benefit school sites. In SFUSD, the central per-pupil expenditures are negatively correlated with enrollment i.e. the more students a school has, the less money the central office spends on the school on a per-pupil basis. This indicates that the district office is paying for the fixed cost of running a school site in an effort to hide how expensive it is to operate small schools. As figures 2-4 show, this negative correlation between enrollment at a school and central per-pupil expenditures for that school is much stronger at the middle (R-squared = 0.69) and high school (R-squared = 0.6) levels than at the elementary school level (R-squared = 0.19)

Evaluating Per-Pupil Expenditures

Let’s consider from now on the total per-pupil expenditures at each school, regardless of whether those amounts are spent directly at the school or indirectly for the school by the district. Figure 5 shows the total per-pupil expenditures at each school as a percentage of the weighted average across all schools, which turns out to be $9,443. All the schools in some shade of blue have less than the average spent on them. All the schools in some shade of orange have more than the average spent on them. I’ve labeled some of the schools to give a sense of the range of values, from Lilienthal at 74% of the average to Lee at 538% of the average.

Although this illustrates that schools in the eastern half of the city generally have a lot more money spent on them, that is not necessarily unfair: those schools generally have more needy students so we would expect them to have more spent on them. Evaluating whether an allocation is fair is inherently subjective: just about any spending allocation can and will be defended by someone on grounds of fairness or equity. One way to approach the issue of the fairness of a district’s allocations is to compare how the district receives its money with how it spends its money.

Comparing Grade Levels

The state’s Local Control Funding Formula gives school districts 20% extra money per high school student. Does this extra money actually make it to the high schools? No. The per-pupil expenditure at SFUSD’s high schools in aggregate is 104% of the amount spent at its elementary schools. I was ready to get all angry at SFUSD for shafting its high school students but I checked other districts and it turns out SFUSD is not an exception. The high-performing districts I regularly track are at 109% (ABC), 105% (Clovis), and 102% (Long Beach) but Palo Alto is at 97% and Los Angeles and San Diego are both at 91%. It appears to be universally true that unified school districts shaft high school students3. A separate high school district would prevent money intended for high school students from being siphoned off by the elementary schools.

Comparing School Allocations By Need

Under the state’s Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF), districts get a 20% bonus for each student who is either eligible for free or reduced price meals, or an English learner, or in foster care. The percentage of such kids is known as the unduplicated pupil percentage (UPP). If a district allocates funds to schools in the same way that it earns money from the state, we would see a direct link between the UPP of a school and the per-pupil expenditure. In reality, while those numbers are correlated, need only partially explains the observed expenditure differences.

Elementary Schools

Figure 6 shows that the the total per-pupil expenditures at elementary schools is only loosely related to that school’s unduplicated pupil percentage (UPP).

The elementary school with the lowest per-pupil expenditure is Lilienthal ($6961). The highest is Lee ($50,780) - so high I had to exclude it from the graph to make the graph readable. Lee is so high because it had only 39 students in 2020-21 (it was staffed for its usual student body size but Lee is a newcomer school and there were few newcomers from China the first year of the pandemic).

Even excluding Lee, there is an enormous range of per-pupil expenditure amounts. Under the LCFF a school with a 100% UPP would earn 20% more than a school with a 0% UPP. Only 23 of SFUSD’s elementary schools are within 20% of Lilienthal PPE. 29 receive between 20% and 50% more than Lilienthal; 13 receive 50%-100% more per pupil than Lilienthal and seven receive at least twice as much per pupil as Lilienthal. Those seven (Lee; the other newcomer school, Mission Education Center; the three Bayview schools; El Dorado; and Cobb) are the seven smallest elementary schools in the city. This is not a coincidence. Small schools are very expensive to run.

Some of the numbers are impossible to justify. The school with the lowest UPP in the city is Miraloma at 16%. The school with the highest UPP in the city is Lau at 94%. Nevertheless, SFUSD spends more per student at Miraloma ($9,220) than at Lau ($8,221). The school level expenditure amounts are smaller at Miraloma than at Lau ($6219 to $6920), which is to be expected, but the central expenditures are greater at Miraloma ($3001 to $1301) and there is no detail available that would shed any light on why.

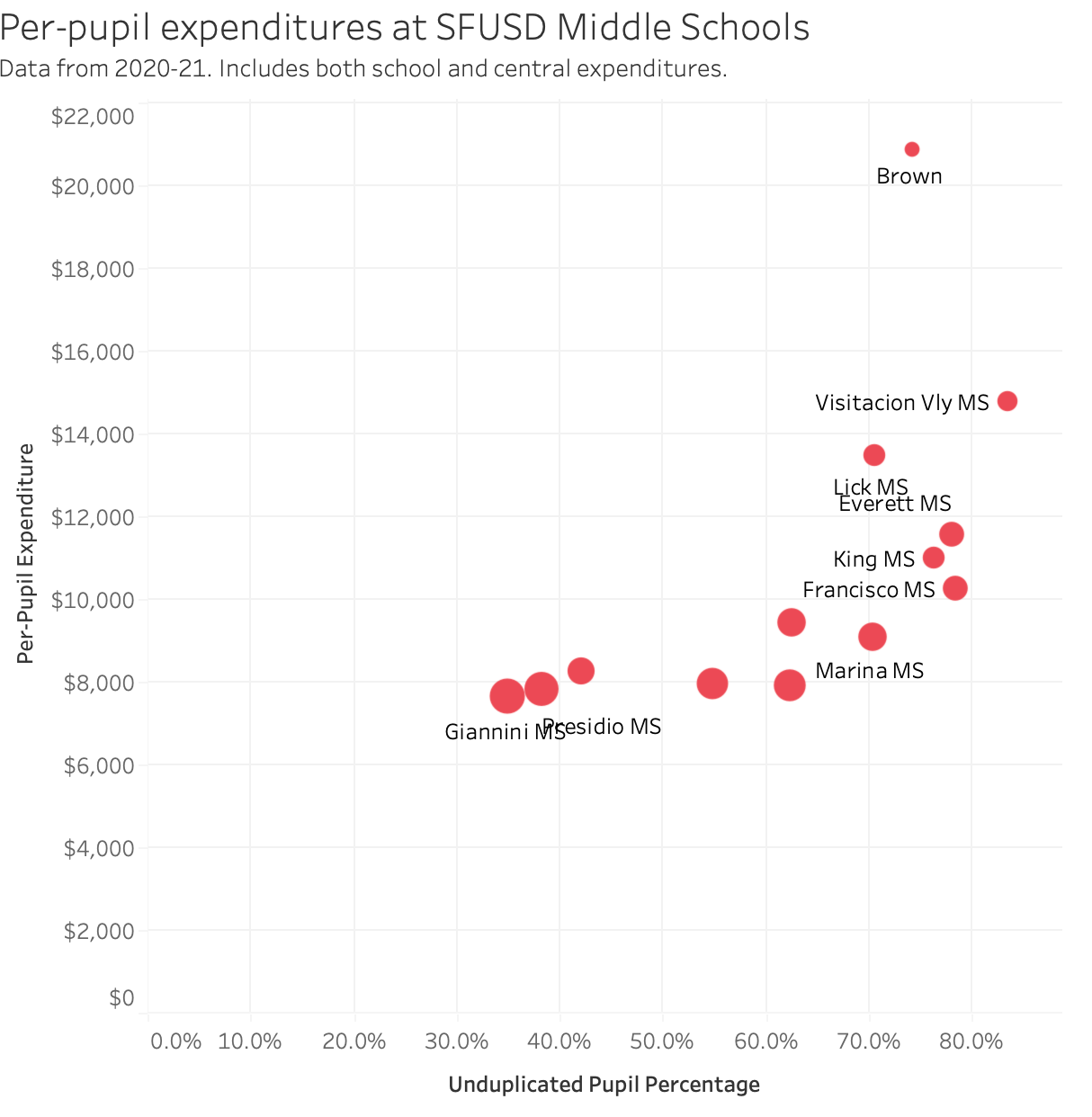

Middle Schools

Figure 7 shows the UPP and per-pupil expenditures for middle schools. AP Giannini has both the lowest UPP and the lowest per-pupil expenditure ($7,666) but, for the larger middle schools, there’s very little correlation between UPP and expenditure. For example, Hoover (UPP: 62%) has only 3% more spent at it than Giannini (UPP: 35%).

Once the UPP gets over 70%, we start seeing some huge differences that can’t be justified by need. Lick and Marina have almost identical UPPs (70.3% vs 70.5%) but Lick ($13,462) has 48% more spent on it than Marina ($9,099). Brown has a lower UPP than Francisco (74% to 78%) but has more than twice as much spent on it per student ($20,860 to $10,257).

High Schools

Figure 8 shows the UPP and per-pupil expenditures for high schools. Asawa SOTA has the lowest UPP of any high school but, at $9,222, it has 20% more money spent on it than Lowell, the school with the lowest per-pupil expenditure ($7,705) and more than Washington, Lincoln, Galileo, and Wallenberg as well.

Mission ($12,726) has 30% more money spent on it than Burton ($9,767) even though Burton has a slightly higher unduplicated pupil percentage (71% to 70%).

Independence High has more than twice as much money spent on it as Washington ($18,700 per pupil vs $8,130) despite having a slightly lower UPP.

The small high schools are super expensive to operate. Continuation high schools tend to be small and expensive everywhere but other districts tend not to have so many other small high schools as SFUSD (Independence: $18,700 for each of 201 students; Jordan $14,975 for each of 253 students; International $14,397 for each of 311 students).

Comparison with other districts

We’ve seen that, at each grade level, there is enormous variation within the city between the best and worst funded schools. No other district that I could find has as wide a range of school funding outcomes as San Francisco. Figure 9 below shows the funding for each school in SFUSD; the high-performing districts I always use as comparators (ABC, Clovis, Long Beach); and select other districts in the Bay Area and beyond. Each dot represents a school. To control for the different funding levels in each district, each’s school’s funding is shown as a percentage of the funding of the lowest-funded school in that district. For example, the lowest funded school in San Francisco is Lilienthal at $6,961 so Flynn’s funding of $9,636 is shown as 138% of Lilienthal’s amount.

In all the other districts, the dots are grouped more closely together indicating that the funding doesn’t vary as much from school to school. (Yes, I know I could quantify this with a standard deviation but the picture is compelling enough to illustrate the point).

In summary, San Francisco’s school funding process leads to results that are more uneven than those found in other districts. That unevenness is partially because SFUSD consciously gives more money to schools with more needy students but primarily because it operates so many small schools that don’t have sufficient enrollment to pay for the staff and services SFUSD provides at those schools.

I’m using www.ed-data.org as the source for all general fund expenditure data.

Per-pupil expenditures are calculated using cumulative enrollment numbers which are higher than the more common census day enrollment numbers.

If you think about it from a political power perspective, this becomes unsurprising. With the smaller class sizes in elementary school, most unified school districts will have a majority of their staff in grades K-5. That’s where the power lies. SFUSD has seven assistant superintendents, five for its elementary schools, one for its middle schools, and one for its high schools. None of UESF’s officers appears to come from a high school. When cuts had to happen last year, both sides were prepared to cut the high school budgets first.

Revisiting an older post but I'm curious if you have thoughts on the impact of PTA funding on schools.

This could be my biased view based on a small sample but it seems that PTA funding can have a great impact on the money available to a school. In my experience, I have seen how much impact PTA money can have funding specific programs (reading aid, gardening, etc) and also freeing up site budget (supplies, etc).

I'm wondering if the PTA money ended up covering some of the funding discrepancies thar you highlight in the article.

Excellent analysis as usual. I hope The School Board reads these. Do you know if they do? If lot, I can mail it to them at least.