Teachers, part 2

The growth in SFUSD headcount over time and the uneven distribution of experienced staff across schools

The previous post compared staffing levels in SFUSD with those in other districts around the state and found that SFUSD employs more staff per student than other districts but cautioned that the data might not be entirely reliable. This post is going to dig in to more detail in two areas:

how employment levels have changed over time

how staff are distributed across the schools of the district.

Employment Growth at SFUSD

The California Department of Education (CDE) tracks the assignments of all staff in all public schools in the state. Staff are classified as having one of three roles: Teachers, Pupil Services, or Administrators. The majority of teachers are assigned to teach specific courses in schools. Elementary school teachers are assigned to spend 100% of their time teaching course code 1000 (“Self-contained class”). A high-school English teacher might be assigned to spend 20% of her time on each of five classes, three of which are English 9 (course code 2130) and two of which are English 10 (course code 2131). Some staff are classified as teachers despite not having course teaching responsibilities. Their jobs are given assignment codes instead. For example, resource teacher is code 6017. Administrators and Pupil Services staff don’t have course teaching responsibilities so they are all given assignment codes based on their jobs (0301 = Principal; 0205 = Social Worker etc.).

By using these codes, we can track the number of people assigned to different jobs in the district and see how those change over time. We can sometimes trace how one individual’s responsibilities change from year to year but we can’t do so reliably because the code (the “recID”) used to identify each staff member anonymously may change from one year to the next.

Change in Headcount Over Time

Here is how district teacher headcount has changed since 2012-13. That is the earliest year for which CDE still publishes data but it is a convenient starting point because it marked the end of a statewide budget cutting cycle.

Enrollment numbers (right axis) hovered in the narrow range of 52,500 to 53,000 before the pandemic knocked them down below 50,000. Meanwhile, reported teacher FTEs (FTE=full-time equivalent) rose by about 7% over four years to before jumping from 3135 to 4312 to 3424 in successive years. Obviously the district didn’t hire 1200 people in 2017-18 only to fire 900 of them the following year. This is clearly a data error.

The district employs more than just teachers. Here is how the evolution of teacher FTEs (left axis) compares to the evolution of pupil services FTEs and Admin FTEs (right axis) over the same period. The number of Admins increased more than 25% from below 250 in 2012-13 and 2013-14 to above 310 in 2018-19. Meanwhile, the number of Pupil Services staff never recovered after the layoffs in 2012-13. But recall from the last post that SFUSD still has more pupil services staff per student than any other district in the state.

I spent an unhealthy amount of time digging in to these records to try to figure out how SFUSD was deploying its staff and what changed between 2016-17 and 2018-19 (and skipping the obviously problematic 2017-18). Here are two treemaps to show the before and after:

What immediately stands out is the huge shift in staffing from school sites (all those small rectangles on the left) to the District Office (on the right):

The huge increase in teachers at the district office is primarily because the number of “Day to day substitute teacher - permanent employee” (code 6014) increased by 798 from 139 to 937. This must be an error of some kind - I can’t believe that the district suddenly hired 800 extra permanent employees to be substitutes. I tried to trace where these additional substitutes came from but was only able to do so for about 100 of them. Perhaps the others are people available to be substitutes or who acted as a sub at least once. I did find a number who appeared to be double-jobbing i.e. teaching a normal courseload at one of the district schools while also appearing as a day-to-day substitute teacher in the district office. The true Stakhanovites among them were holding full-time jobs in other districts while also appearing as permanent day-to-day substitutes in SFUSD’s district office. Most of these other districts were in San Mateo, Alameda, or Marin but there were some as far away as LA and Ventura counties. I suppose that could be evidence of fraud but I suspect it’s evidence of bad data.

The number of teacher FTEs assigned to teach courses at school sites went down from 2495 to 2155 between 2016-17 and 2018-19. Two thirds of the reduction was due to cuts in consultation/instructional support (code 3020), self-contained class (code 1000), homeroom/study hall (code 6002), and skills center/study skills (code 6001). I believe that “Consultation/instructional support” was the code used for art and music classes and that the idea was to stop employing these teachers directly at school sites but to employ them out of the district office and then assign them to schools. This was presumably done for equity reasons (every action is justified by equity) but it does have the effect of obfuscating staffing practices.

Over 200 “other certificated non-instructional assignments” (code 6020) were removed from school sites. I was able to trace what happened to about half of the teachers who held those positions: most became normal teachers with course assignments with a small number becoming permanent day-to-day substitutes.

The number of teachers working on Peer Assistance and Review (code 6011) increased from 115 to 151. These are also part of the District Office headcount. With 2155 teachers actually teaching courses, that means there was one peer reviewer for every 14 classroom teachers. The purpose of peer assistance and review is to “provide assistance and support to teachers whose bi-annual personnel reviews were not satisfactory” which suggests that either SFUSD has a huge number of unsatisfactory teachers or there were too many peer reviewers. One of the changes the district has been forced to make since the pandemic is to reassign peer reviewers to the classroom to fill unstaffed classrooms. This has annoyed many of those teachers since peer assistance was seen as a cushier job.

The number of Pupil Services staff increased by nearly 30% over the two years to 538. The number of psychologists more than doubled to 70 while there were 109 social workers, 73 speech-language pathologists, and 47 nurses. These roles had previously been assigned to specific school sites but they were all moved to the district office. This 30% increase should not be interpreted as representing a big investment in pupil services. Instead, it merely restored most but not all of what had been cut between 2015-16 and 2016-17. (It’s not clear to me whether the 2016-17 cut was real or another data error).

65 administrators with assignment code 0131 (“Admin library/media services”) were replaced by 63 teachers with assignment code 6027 (“Non-instructional teacher librarian”). I smiled when I saw this. I doubt that anyone’s responsibilities changed but this reclassification would have had the effect of reducing measures of administrative costs.

The number of other administrators increased by 19 to 311, split roughly 60:40 between school sites and the central office. The administrators at school sites are principals and vice-principals. Those in the district office have the nebulous roles of: “Admin staff personnel services” (code 0107), “Admin other program” (code 0126) and “Admin other school level services” (code 0307).

Teacher Distribution

Hiring and retaining talent is a challenge for every school district. Schools within a district compete for talent with each other. Those that are seen as good places to work (because of some combination of an effective principal, congenial colleagues, supportive parents, and attentive students) will hold on to staff longer and find it easier to fill positions than schools that are not seen to be as good.

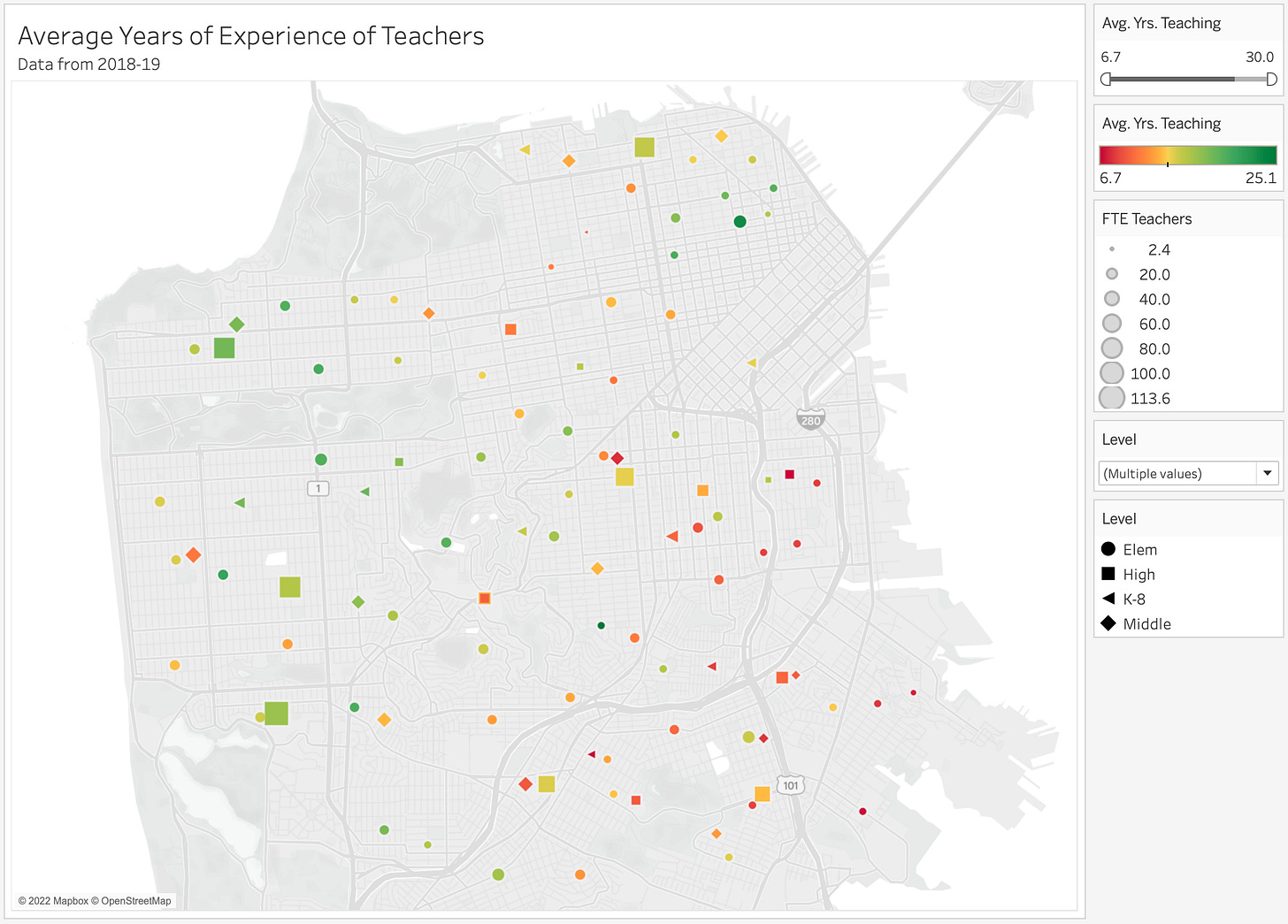

We saw in the last post that the average experience of SFUSD’s teachers was very much in line with statewide averages. But there are enormous differences when we look from school to school. Here’s a map of the average experience of teachers at each district school.

Most of the schools where the teachers average more than twenty years of experience can be found in the Sunset or Richmond or near Chinatown. All the schools where the average teacher has fewer than ten years of experience can be found in the south-east corner of the city. Black and Latino kids are disproportionately represented in those schools so they have less experienced teachers on average. The teachers of Black and Latino children average 13 years of experience1 while those of White children average 14.6 years of experience and those of Asian children average 15.4 years of experience.

Since most of the lowest-achieving schools can also be found in the south-east, the correlation between teaching experience and student achievement must be quite strong in San Francisco. But it’s unclear whether one causes the other. Do students perform poorly because their teachers are inexperienced or do schools whose students are performing poorly have difficulty attracting and retaining teachers? I haven’t tried to quantify the importance of teacher experience because any serious attempt to do so would have to control for the demographics of the schools and that’s way beyond the scope of what I want to cover today.

An average can be distorted by a few teachers with 30 years of experience. Let’s also look at the percentage of staff who are inexperienced which I’ll define arbitrarily as those with four or fewer years of experience. Across all the district’s schools, 17% of staff were inexperienced but the range was enormous. Eight schools had no inexperienced teachers at all. Another seven had fewer than 5%. These schools have few vacancies and are able to fill those that do occur by recruiting experienced teachers from other schools. At the other extreme, 40% or more of the staff at Brown MS, Harte ES, El Dorado ES, and Drew ES were inexperienced2. They have trouble retaining staff and vacancies get filled by inexperienced teachers.

Hard-to-staff schools

What could the district do to equalize experience levels across the district? One obvious answer is to pay teachers more to work in the unpopular schools. Before the Quality Teacher and Education Act (QTEA) was put to voters in 2009, the district and the union negotiated in advance how to spend the money it would raise. One provision awards additional pay to teachers in a list of hard-to-staff schools and to teachers of hard-to-staff subjects. According to one description of that negotiation:

…bonuses for teachers in hard-to-staff schools took some careful negotiation. Union leaders stressed that they “will not agree on anything that smacks of ‘combat pay,’” which is money given to teachers as a bonus for working in schools perceived as difficult. The district and union were able to come to agreement on this provision by reframing the bonus as “extra pay for extra work,” reflecting the additional hours that are often contributed by teachers in hard-to-staff schools.

The district has lately taken to calling these hard-to-staff schools “high potential schools”, the sort of phrase that would provoke George Orwell. The stipend that the district pays to teachers in hard-to-staff schools is something like $2000, which is less than 4% of the lowest salary offered by the district and less than 2% of the highest salary. It’s hard to believe that’s sufficient to sway the behavior of many teachers. In comparison, the US state department offers post differentials of up to 35% and maintains a detailed list of which cities merit which differentials. The differentials are meant to “compensate employees for service at places in foreign areas where conditions of environment differ substantially from conditions of environment in the continental United States and warrant additional compensation as a recruitment and retention incentive.” The least attractive sounding post may be Ammo Depot #9 in South Korea but that only merits a 5% differential. In fact, many places that have different “conditions of environment” and merit non-zero differentials are popular places to live and visit. Dubai and the Bahamas are at 5%, Buenos Aires and Rio de Janeiro and Cape Town at 10%, Kuala Lumpur and Mexico City and Durban at 15%, Belize and Shanghai and Saint Petersburg at 20%. A non-zero differential is thus not a diss of the location. It’s just a recognition that the working conditions are different. Does anyone really believe that working conditions at, say, Carver ES in Bayview are the same as those at Claire Lilienthal in Presidio Heights?

Have the existing stipends made a difference? Here is the same inexperienced staff data as above but just limited to those schools that were originally designated hard-to-staff. It’s a mixed bag. The majority of the schools still have large numbers of inexperienced staff but some (viz. Burton HS, Mission HS, Sanchez ES, Cleveland ES) are doing very well and have far fewer inexperienced staff than the district average. I can’t find the current list of hard-to-staff schools so I don’t know if those schools are still on the list, but they probably shouldn’t be.

Another way to increase the average experience of staff in these hard-to-staff schools would be to shield them whenever the district has to do layoffs. In 2012-13, when the district was faced with having to do layoffs, it attempted to exempt teachers in some hard-to-staff schools on the theory that:

we have invested millions of dollars in additional salary, professional development, and other resources in the chief asset of the […] schools: their people. To simply drop them into a seniority-based layoff, [the superintendent] argued, would represent a waste of that investment.

But an Administrative Law judge sided with the UESF which argued that layoffs should be done strictly by seniority.

Does Experience Matter?

All of the above rests on the assumption that more experienced teachers are better teachers. That seems self-evidently true. In every profession, we expect an experienced practitioner to be better than a novice. A teacher with ten years’ experience should be a lot better than a teacher with just one year of experience.

There are five charter schools in San Francisco that primarily serve Latino and Black students (Edison, Mission Prep, and three KIPP schools). Their students perform far better than comparable students at SFUSD schools. But their staffs have less experience than those of any other schools in the city. How can the least experienced teachers be producing the best results? Are the charter schools better at identifying teacher talent? Is the pedagogical approach of the charter schools so much better than SFUSD’s that inexperienced charter school teachers can be more effective than more experienced teachers in SFUSD?

Teacher Experience by Race/Ethnicity

One final observation. I had expected that the White teachers would be older and more experienced than other teachers but that’s not true. In comparison with White teachers (average age 45.6 with 13.7 years of experience), Black teachers are both older (48.6) and more experienced (15.1), Latino teachers are both younger (40.8) and less experienced (11.7), while Asian teachers manage the nifty trick of being younger (43.1) and more experienced (15.5).

I calculated the average teacher experience for students of a particular group by taking the average teacher experience at each school and weighting them by the number of students from that group at each school. For example, if the teachers at schools A, B, and C have 10, 15, and 20 years of experience respectively and the schools contain 300, 200, and 100 Latino students, then the average experience level of a teacher of an average Latino student is ((10 * 300) + (15 * 200) + (20 * 100)) / 600 = 13.3.

I’m ignoring SF Public Montessori even though it had an ever higher percentage (59%) because the data shows that school as having only 3.4 FTE staff

"How can the least experienced teachers be producing the best results?" -- these charters are filled with students from self-selected families that prioritize things like test scores. It seems obvious that they would have better test results, regardless of who the teachers are.

I believe schools with less experienced teachers have smaller classes, which could compensate for less experience. There are also other factors that may determine teacher quality: additional credentials and graduate degrees.

The Colman Report found that the “cause” of student performance was family background not the school. There is a relationship between the percent of Black and Latino students at a school and school performance. There is also an ethnic gap at the same schools with the same teachers. I would guess schools that perform poorly have difficulty attracting and retaining teachers, not that inexperience causes poor performance.

Don’t teachers with more seniority have priority for school assignments?